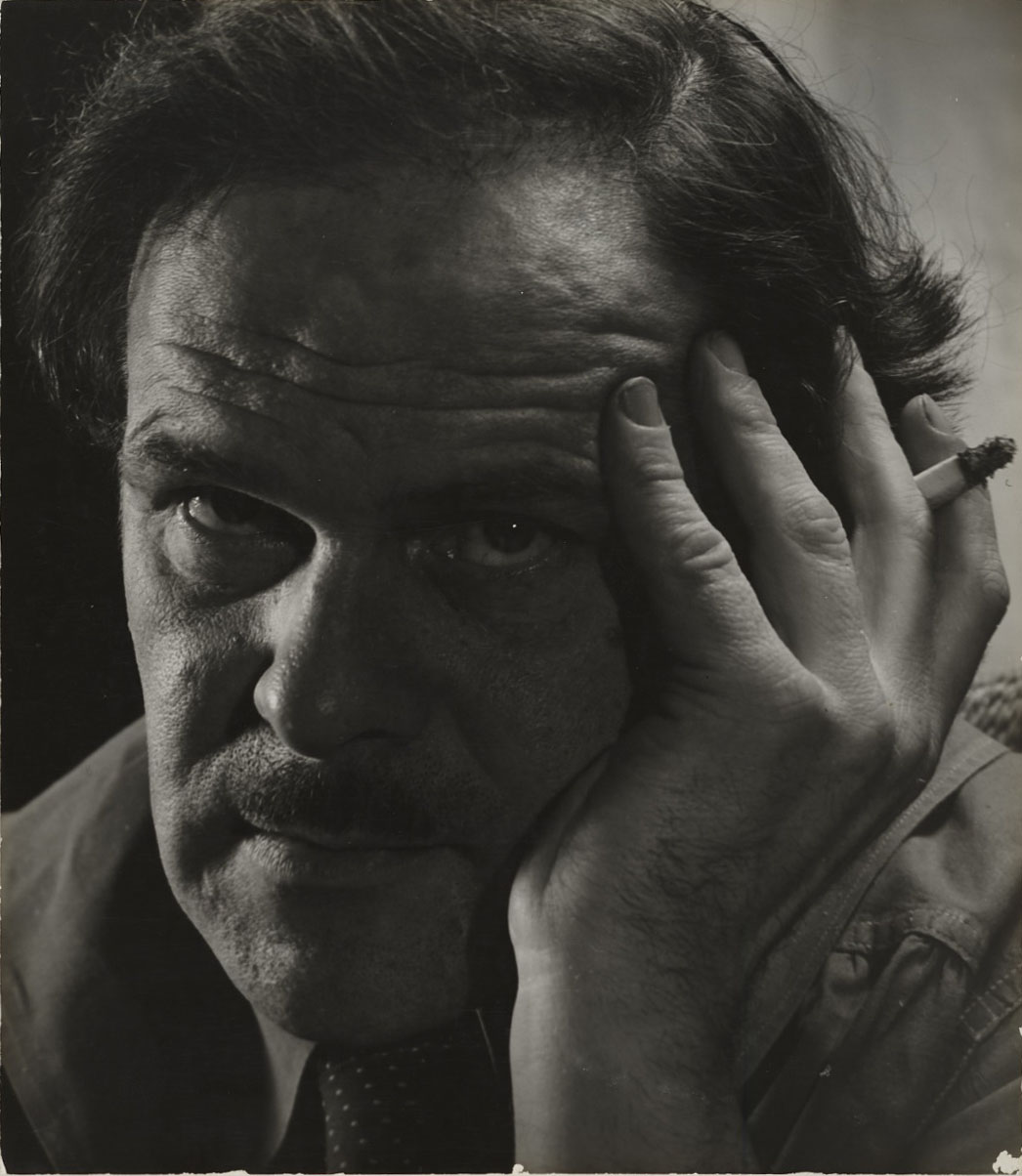

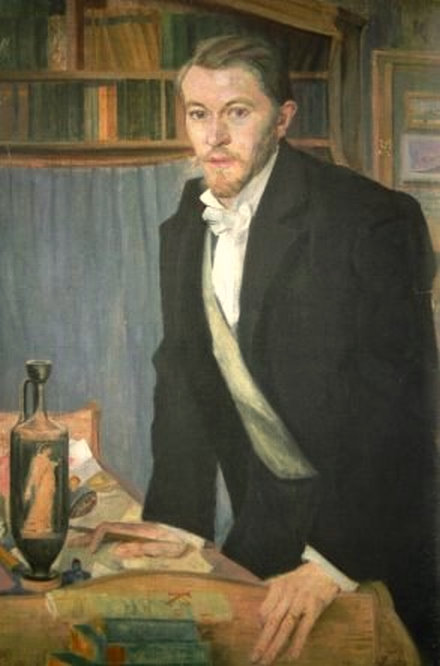

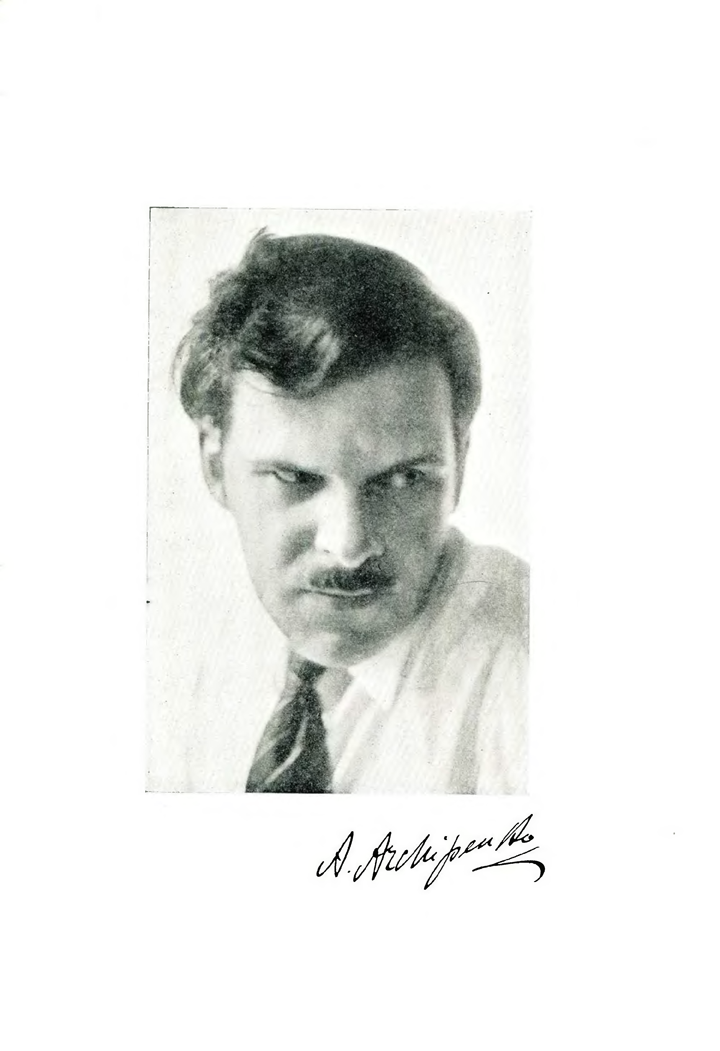

Archipenko Oleksandr

Oleksandr Archipenko (1887-1964) is a Ukrainian-American sculptor, artist, and teacher. An innovator in art, he was probably the first to start making sculptures with movable elements using “nonclassical” materials: wood, glass, and wire. He is also one of the first cubist sculptors.

In general, art scholars and critics quote over 20 innovations Archipenko introduced in art. From his father Porfyriy, a mechanical engineer who managed labs and physics classrooms at Kyiv University, Alexander took an inventive approach, combining it with critical thinking and independent mastery of museum art heritage. He did not want to follow any known style, so he was able to invent a new language and lay down avant-garde principles in the paradigm of the 20th century.

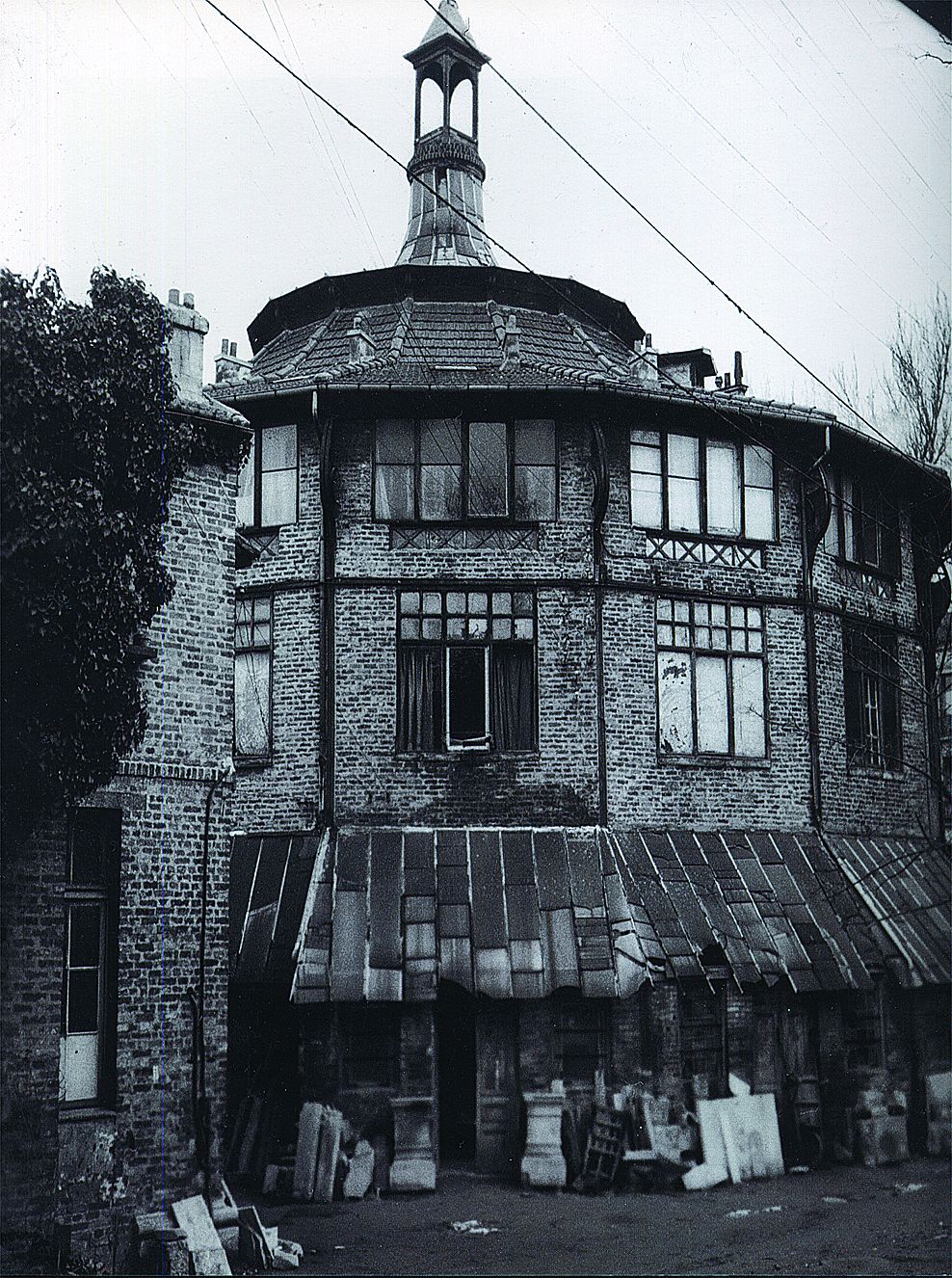

2 Passage de Dantzig, Paris, France

From 1908 through 1909, room No. 58 in La Ruche, a famous art colony, was occupied by Alexander Archipenko, sculptor. Originally from Kyiv, he had come to Paris a short while before and immediately found himself at the centre of Montparnasse bohemian life. Here he met scores of peers among experimental artists—Amadeo Modigliani, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Ossip Zadkine, Constantin Brancusi, and Fernand Leger, the latter soon becoming Archipenko’s close friend. During his first years in Paris, when young artists were routinely penniless, they took a harmonica and wandered through the city—from Vaugirard street to Belleville boulevard (from Montparnasse to Montmartre). Leger played the harmonica accompanied by Archipenko’s “warm and rich” baritone.

It was in La Ruche that the Ukrainian artist met French avant-garde poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire. Later, Apollinaire would write a great deal about the sculptor, writing that would play a significant role in his career.

The wanderer from Kyiv lived in the art colony for just a year. Despite a moderate studio rent price he did not feel comfortable there. La Ruche had 140 workshops, each of them a narrow, triangular space. With time, Archipenko confessed, “I could not stay there long, it was very uncomfortable. You got the impression you were living inside a hunk of Gruyere cheese.”

Later, the sculptor rented workspace elsewhere. However, all of them were located in Montparnasse, a Paris neighborhood far from the centre, popular among artists for its low rents.

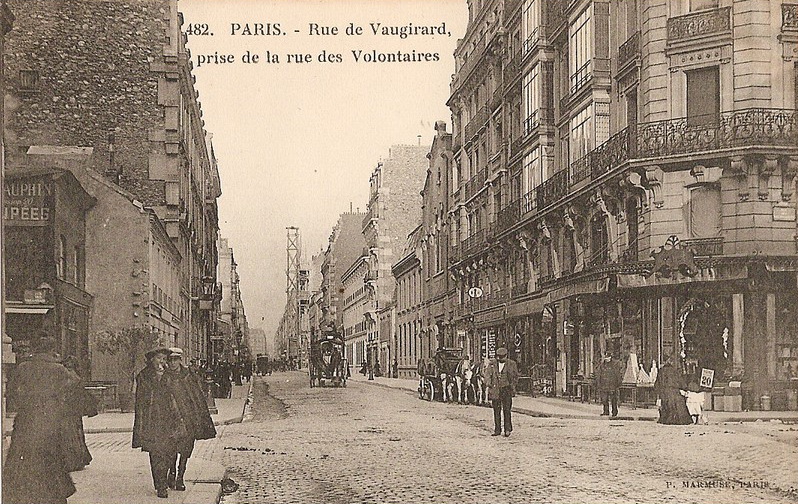

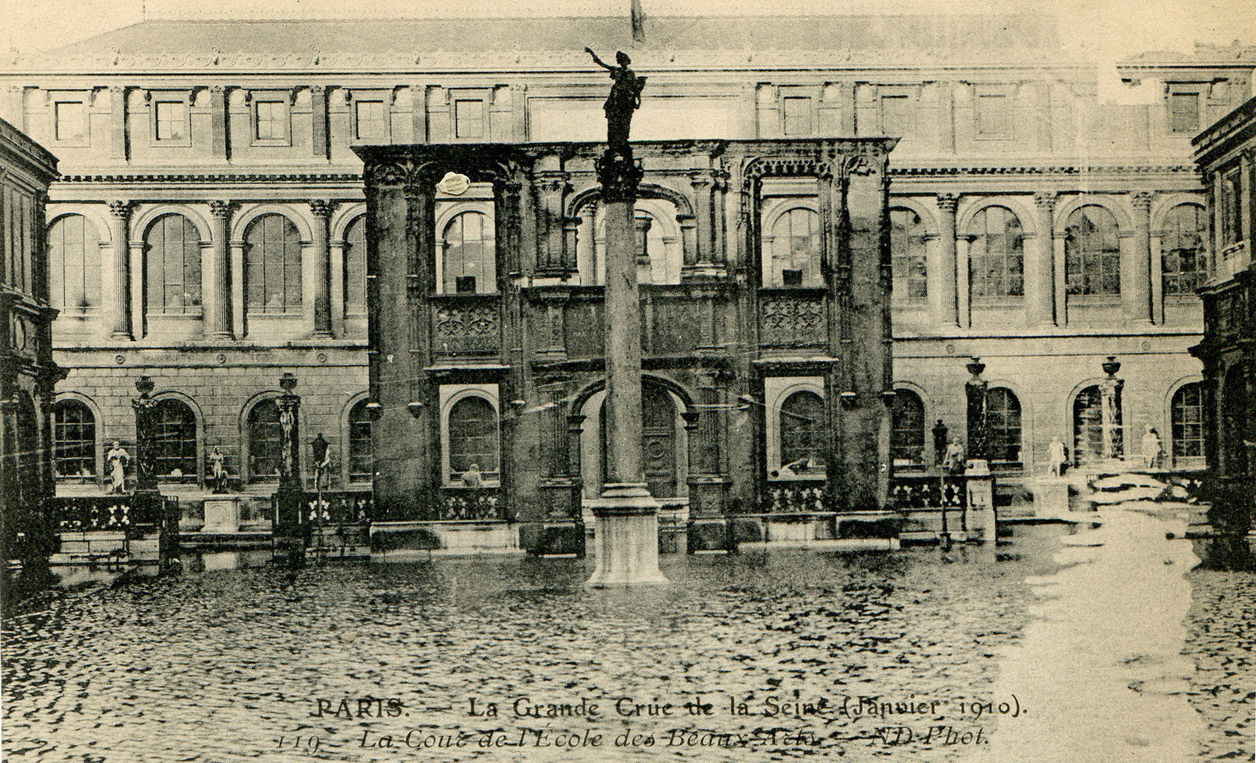

14 Rue Bonaparte, Paris, France

In 1908, Oleksandr Archipenko attended École des Beaux-Arts. However, he only studied here for two weeks. The school turned out to be too conservative. The academic spirit, unacceptable to the artist, dominated here just as it did at Kyiv Art College where he studied for three years (1903-1905) and at the Moscow College of Art, Sculpture and Architecture which he attended in 1907.

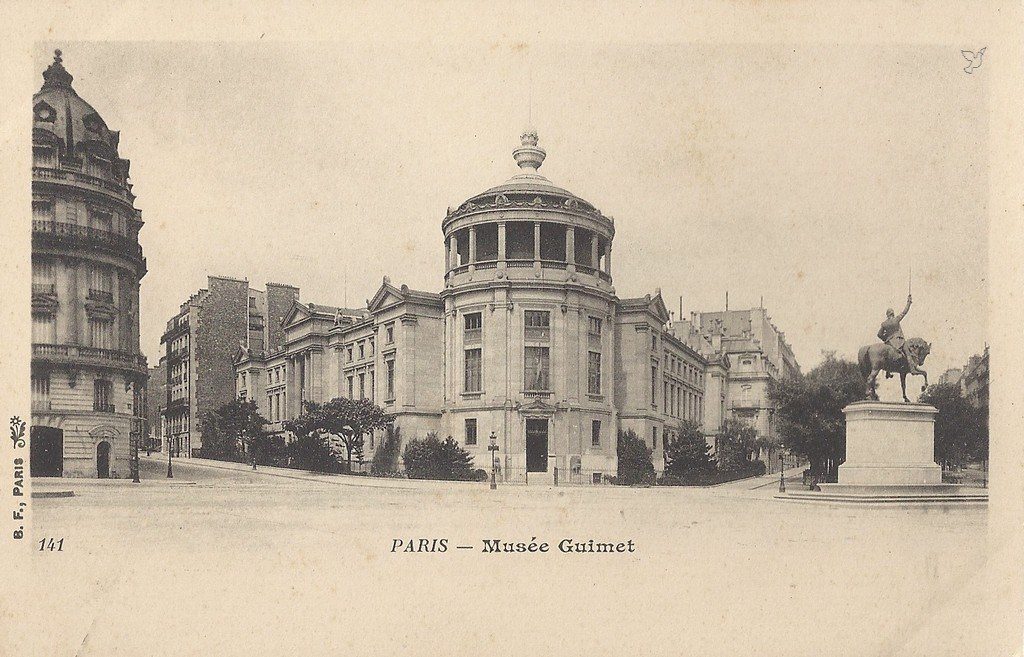

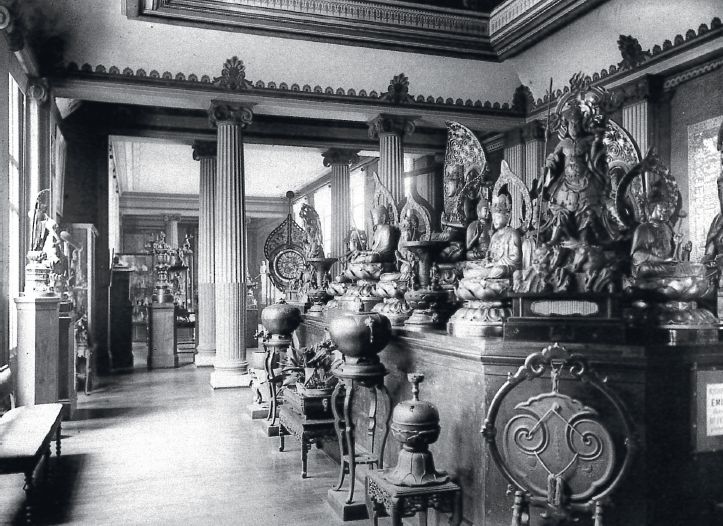

Oleksandr Archipenko decided to study independently. The Paris museum collections became his school; he went to the Louvre, Trocadero Ethnography Museum (now Museum of Human), and eastern art collection at the recently opened Guimet museum. “My real school was the Louvre,” Archipenko recalled. “For several years I went there every day. I mostly worked with archaic art and all the grand, dead styles. At first, I worked under the influence of these styles and had a hard time breaking free from them. But I did it and found my own style.”

Cours la Reine, 75008, Paris, France

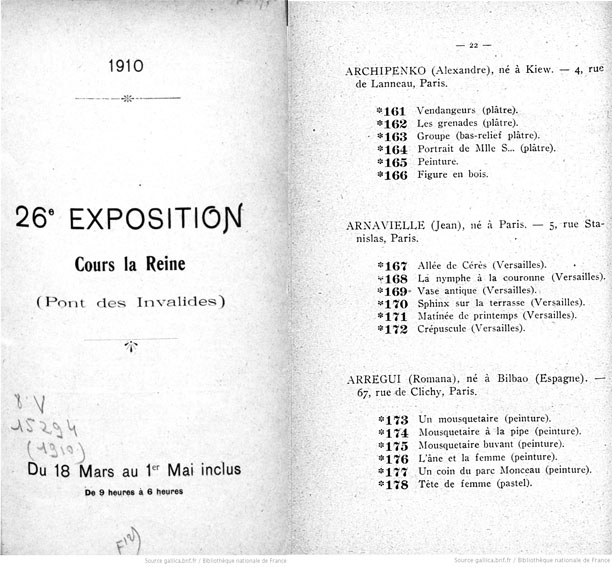

In the spring of 1910, in specially constructed temporary facilities at Cours-la-Reine quay, the 26th Salon of Independent Artists took place. It was a large annual exhibition, presenting works by cubist artists for the first time, including sculptures by Alexander Archipenko. This was the Paris exhibition debut of the Ukrainian artist. Despite belonging to the cubist group (Robert Delaunay, Henri Le Fauconnier, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Leger, Jean Metzinger, Marcel Duchamp, Raymond Duchamp-Villon), Archipenko’s exhibited works had not yet acquired specific cubist features. These were, rather, his first experiments with plastics resulting from his museum studies.

“My style stems from Assyrian, Egyptian, Indian, early Byzantine, Gothic and Ancient Greece art, not from African sculpture or Picasso,” Alexander Archipenko said.

Grand Palais, 3 Avenue du Général Eisenhower, Paris, France

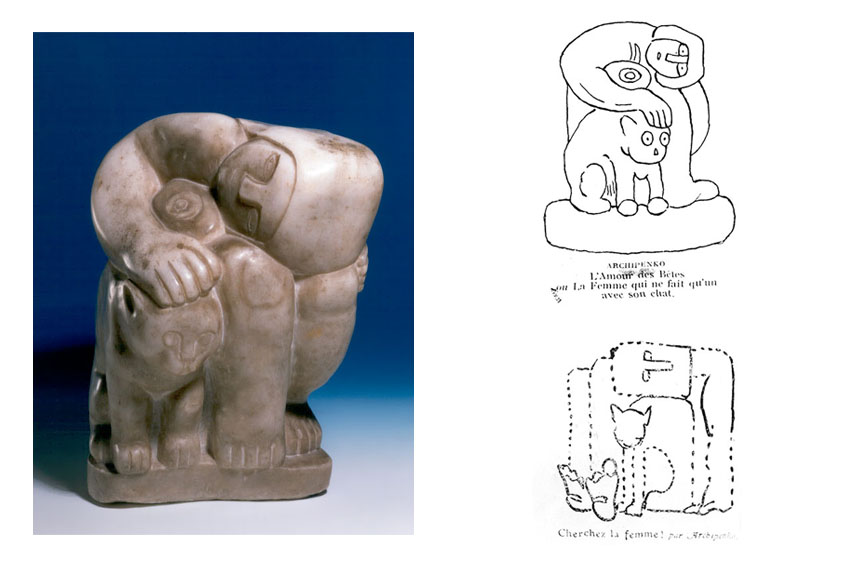

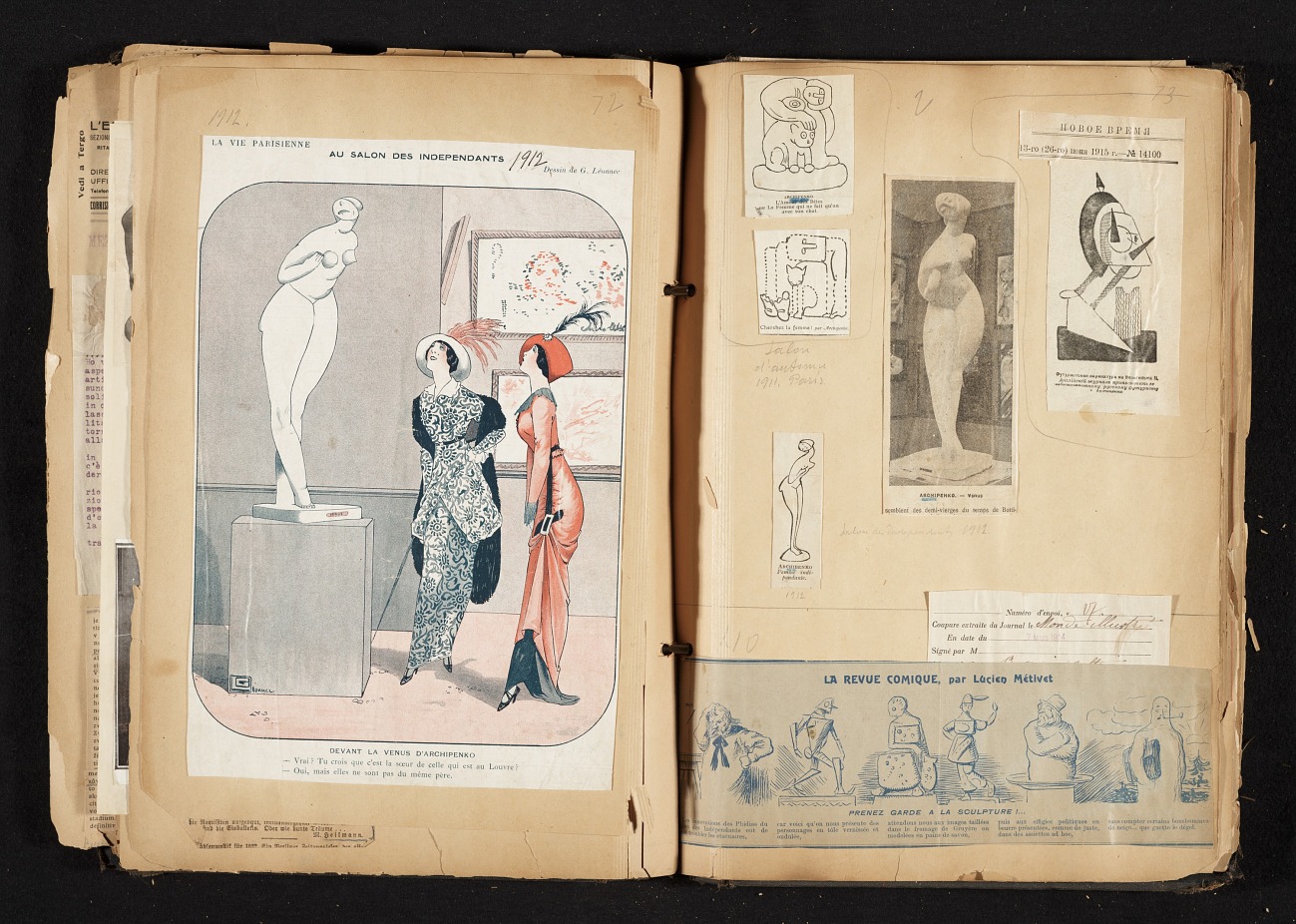

From 1 October 1 until 8 November 1911 in Grand Palais the 9th Autumn Salon was taking place; it was an annual exhibition of modern art where Oleksandr Archipenko participated for the first time. The artist immediately became famous or, rather, notorious. His works provoked misunderstanding and ironic comments from both the audience and the critics. In particular, his sculpture A Woman with a Cat was published on the pages of a French newspaper as a caricature with a mocking caption “Cherchez la femme” (Find the Woman).

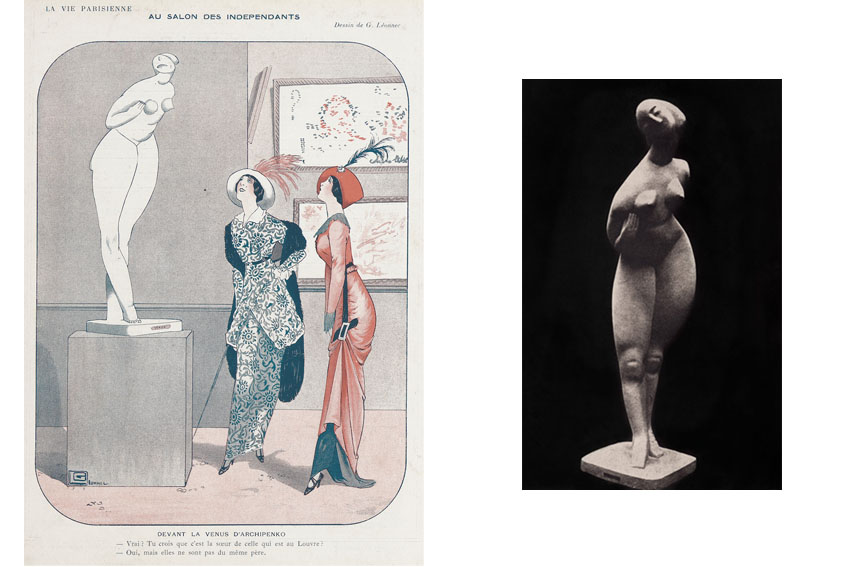

The reputation stuck to Archipenko from then on. The following year, a caricature by Georges Leonnec published in the Paris weekly La Vie Parisienne on 30 March became widely popular. It pictured two ladies standing in front of Venus by Archipenko in the Salon of Independent Artists which took place in specially constructed facilities in quay d’Orsay. “Do you really believe she is the sister of the one in the Louvre?”, one lady asks. “Yes, but they have different dads,” the other answers.

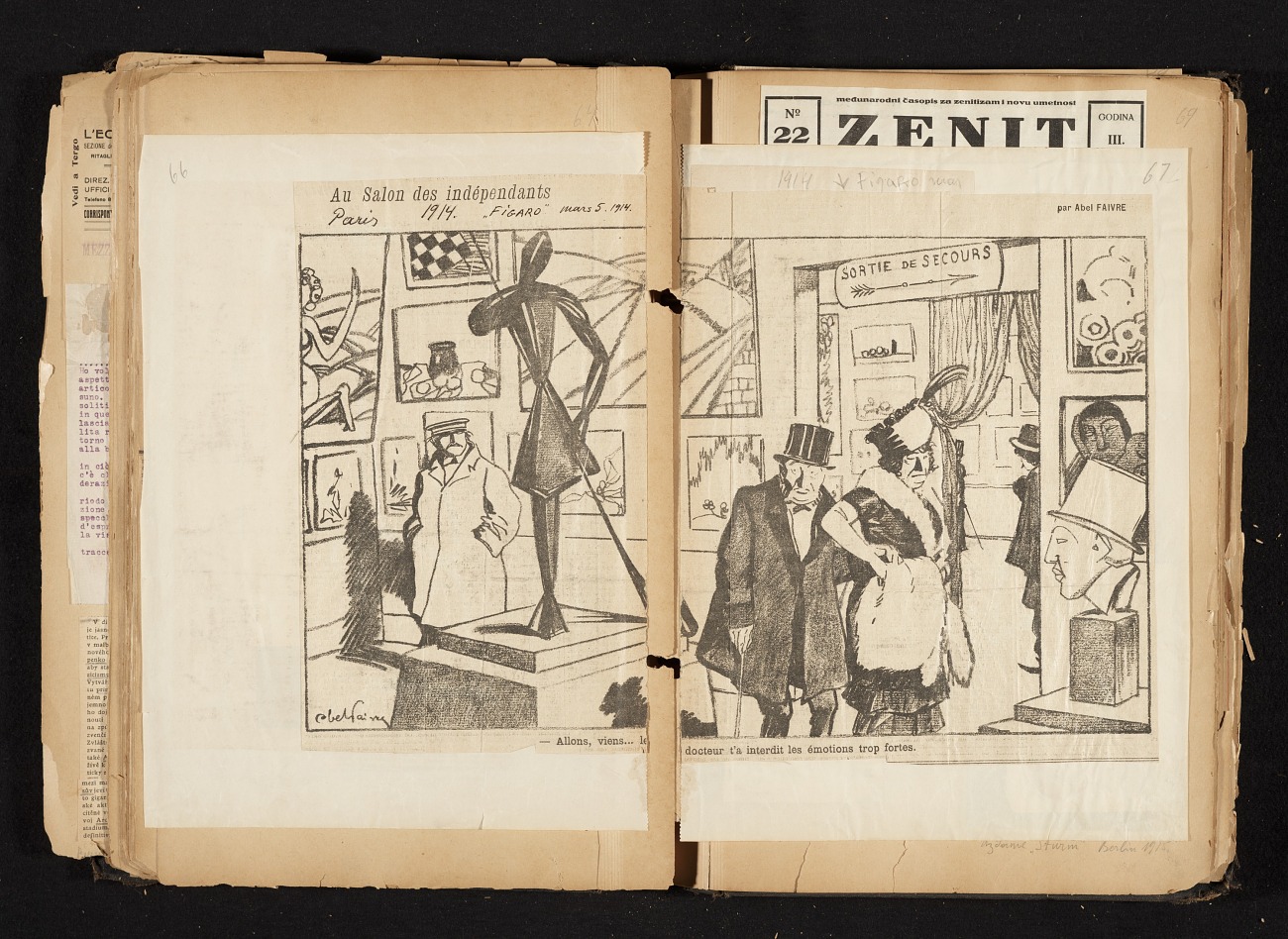

The works exhibited in the Salon of Independent Artists of 1914 provoked lots of sharp statements in the press. In particular, one article was published under a telling title, “Scandal” (Le Bonnet Rouge – 7 March 1914).

Only a narrow circle of artists and writers grasped Archipenko’s courageous creative approach - among them Guillaume Apollinaire, Blaise Cendrars, Maurice Reynald, Fernand Leger, and Henri Le Fauconnier.

Museumspl. 1, Hagen, Germany

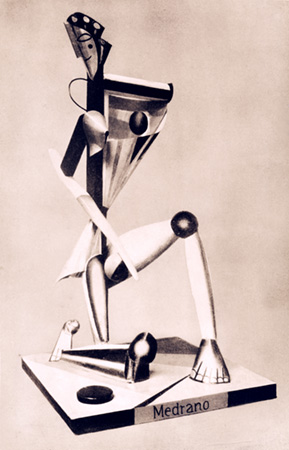

The first private exhibition of 25-year-old Alexander opened on 7 December 1912 in Hagen, in the first German museum of contemporary art founded in 1902 by collector and philanthropist Karl Ernst Osthaus (now Osthaus Museum Hagen). At this exhibition, among other things, the artist showcased his innovative 3D polychrome sculpture from wood, glass and metal, Medrano I. The author of the introduction to the exhibition catalogue was none other than Guillaume Apollinaire, a passionate fan of Archipenko’s art.

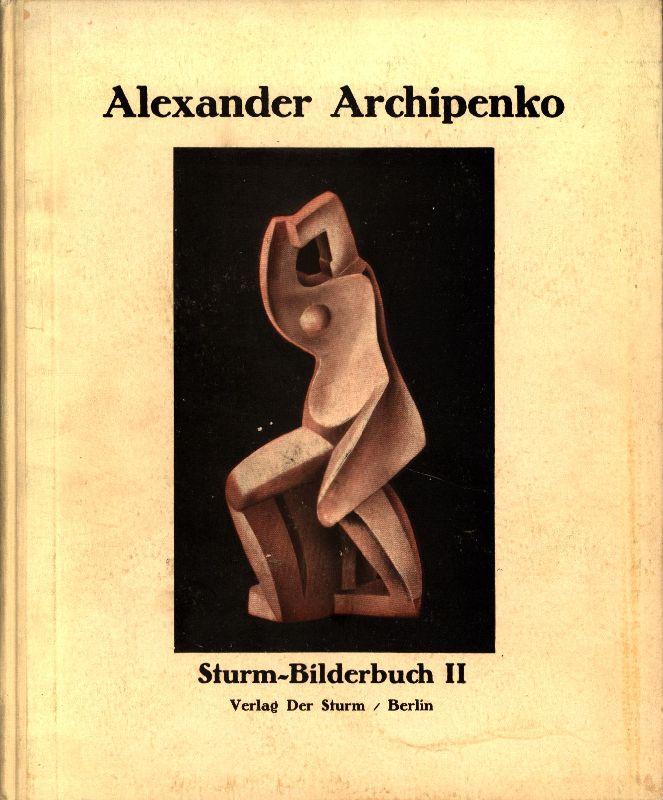

During this period, the rebellious sculptor held numerous exhibitions in Paris, eventually opening his own art school. However, it was in Germany where talk of his genius first surfaced. Prior to World War I, Archipenko held exhibitions in Bremen, Berlin, and Halle.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 5th Avenue, New York, NY, USA

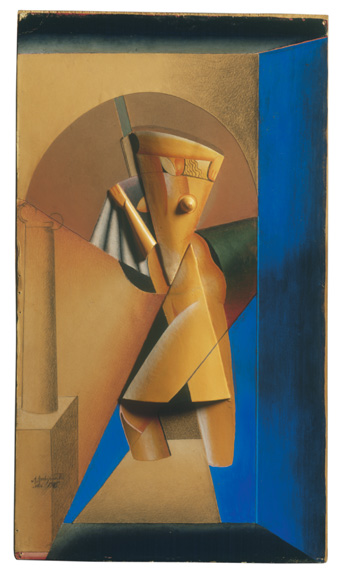

The collection at Guggenheim Museum in New York includes one Archipenko piece that may be listed among the key works of 20th century sculpture: Carrousel Pierrot. The gypsum figure in bright local colours was created by the Ukrainian artist in Paris in 1913. It was exhibited in the Salon of Independent Artists (1914), but the Paris audience and critics did not take to it. All because the author broke one of the main principles of classical sculpture, i.e. monochromatism. Since the Renaissance it has been held that to achieve integrity of form, a sculpture must be only in one colour, namely the colour of the material it was made from. For Archipenko, shape and colour became qualities complementing each other and creating a new optical language. The sculptor revived the tradition of polychromatic sculpture in the art of the 20th century. As for his theoretical reflections on that topic, he laid them out in his Polychromatism Manifesto written in the 1910s.

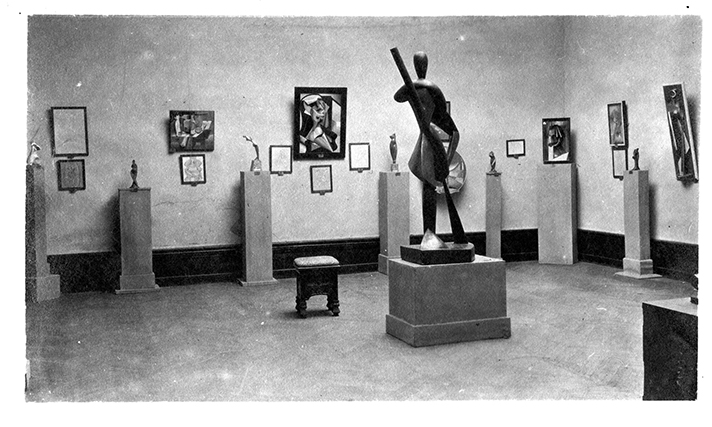

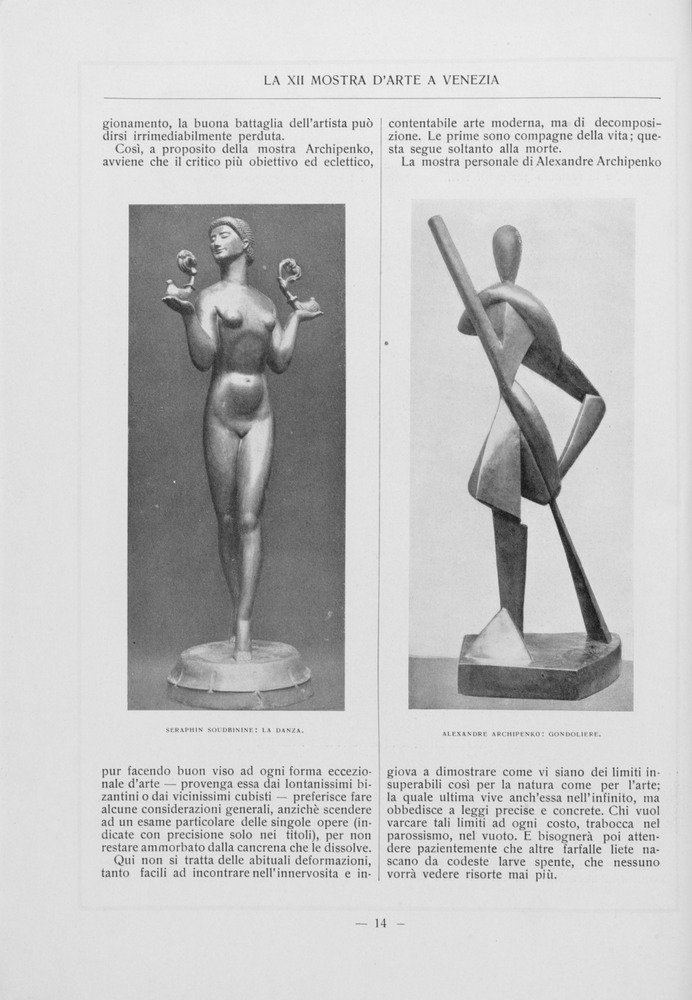

For the Venice Biennale Oleksandr Archipenko selected 48 works. He was exhibited in the Russian pavilion built in 1914 under the auspices of the Russian empire, and funded by Bohdan Khanenko, Ukrainian entrepreneur, collector and philanthropist. Archipenko was allocated a separate hall. In the middle sat his Gondolier sculpture as homage to the artist’s genius. Near the walls stood numerous nudes – a bathing woman, a woman brushing her hair, a woman next to the mirror, a woman sitting in a squatting position and others - which were interspersed with “sculpture paintings”.

Archipenko’s art experiments were well ahead of their time, and both critics and audiences, not knowing how to react to these innovations, routinely and largely reacted negatively. Non-radical critics call him “the most disputable figure in contemporary art”. The Roman Catholic Cardinal from Venice, Pietro La Fontaine, refrained from comment on the works of Archipenko, except to say that he “has distorted the image of a human created in God’s image”, and subsequently forbidding churchgoers from seeing the artist’s work.

However, the public was intrigued by the strange, hollow figures and the colourful “sculpture paintings” that incorporated elements of sculpture, art, and architecture. Archipenko’s work was a tremendous draw at the biennale. And legend says that the password among Venice gondoliers that summer was “Ar – chi – pen – ko”.

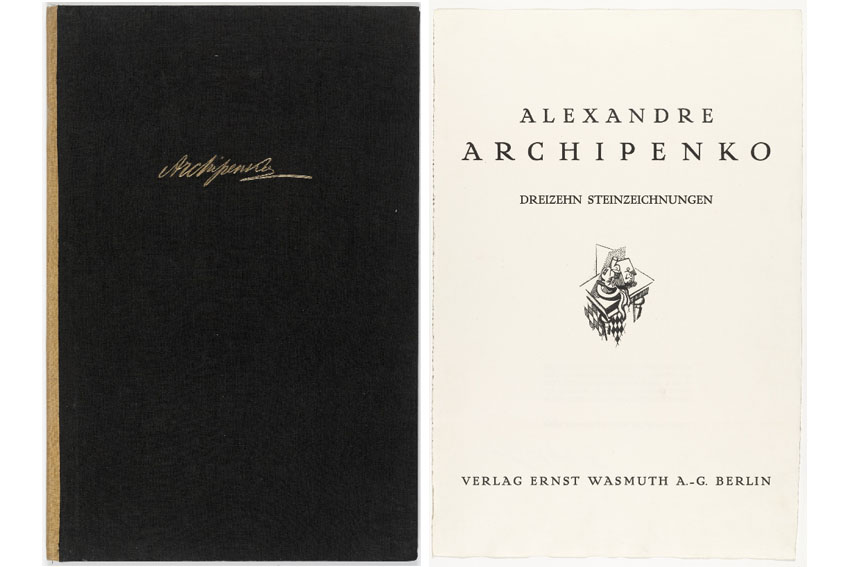

Potsdamer Straße 134a, Berlin, Germany

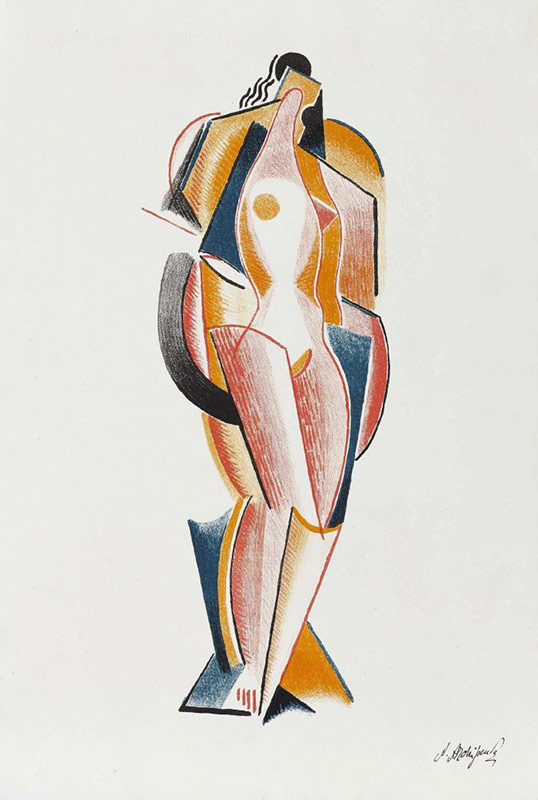

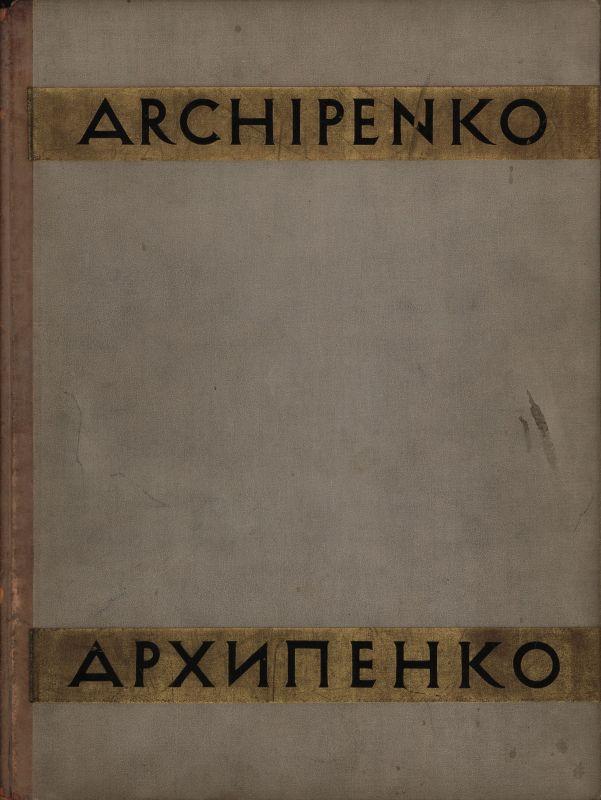

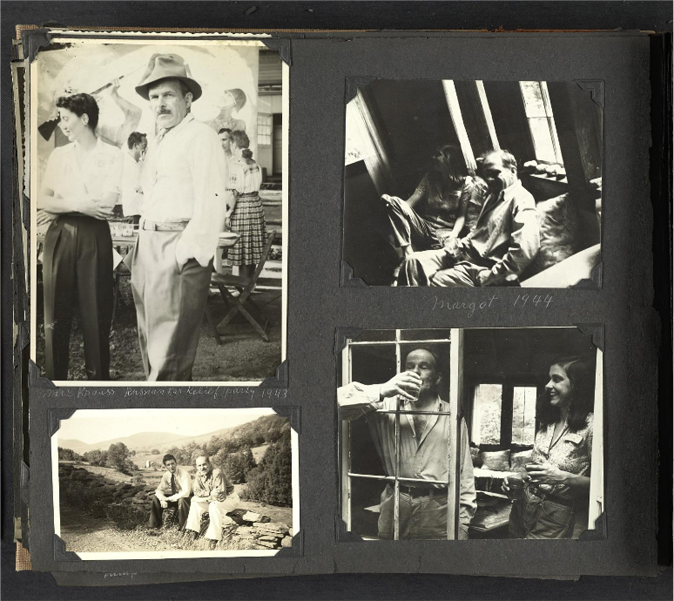

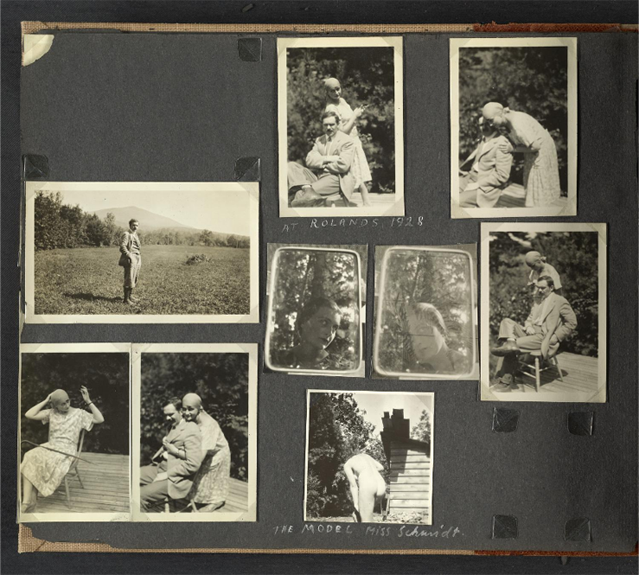

In 1921, two important events took place in the life of famous artist Alexander Archipenko: 1) he moved from Paris to Berlin and opened a school there; 2) he married Angelica Schmitz (1893-1957), a German sculptor working under the pseudonym of Gela Forster, an intellectual and member of the expressionist artists group “Dresden Secession – Group 1919”. The third event is also essential – Ernst Wasmut publishes 60 copies of an elegant portfolio “Alexander Archipenko. Thirteen lithographs” under a cover rendered in black textile with Archipenko embossed in gold. The artist would soon grow into his newfound fame: from 1920 to 1923 in Europe he had 25 exhibitions organized and four monographs about him published.

In the 1920s, a large Ukrainian diaspora began to form in Berlin. From 1922 to 1923 another Ukrainian modernist lived there, celebrated film director Alexander Dovzhenko. The author of classic cinematographic works like Earth, Arsenal, Zvenigorod said he borrowed from Archipenko “courage in bringing art impulses to life and the wish to avoid external precision which was then considered the only way for art to be understood by workers and peasants.”

Germany proudly assigns Archipenko prominence as one of the most interesting sculptors of the time. However, when inflation and economic crisis eat away at the financial rewards stemming from his artistic success, in 1923 Alexander and his wife Angelica sail to the USA where the sculptor has previously held a number of exhibitions of his work.

German gallery and museum curators were interested in Archipenko’s creative practice during different periods of his life and organized many private exhibitions across Germany. German museums currently house some of his greatest work—both his early shape-forming experiments and more mature sculptures of the late American period.

In 1960, Saarbrucken museum hosted a large retrospective of Archipenko’s heritage at which the sculptor donated over 100 of his works to the museum. This collection at the Saarlandmuseum is now the assemblage of Archipenko’s work in Europe.

489 Park Ave & East 59th Street, New York, United States

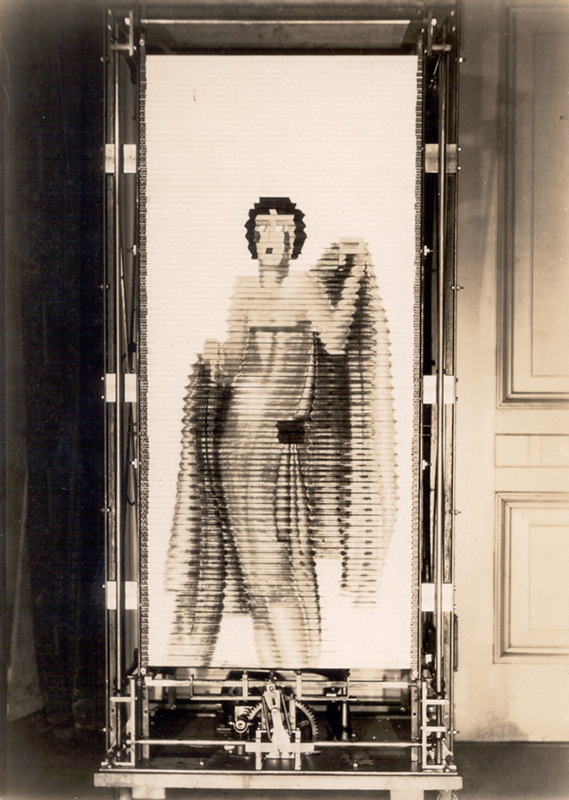

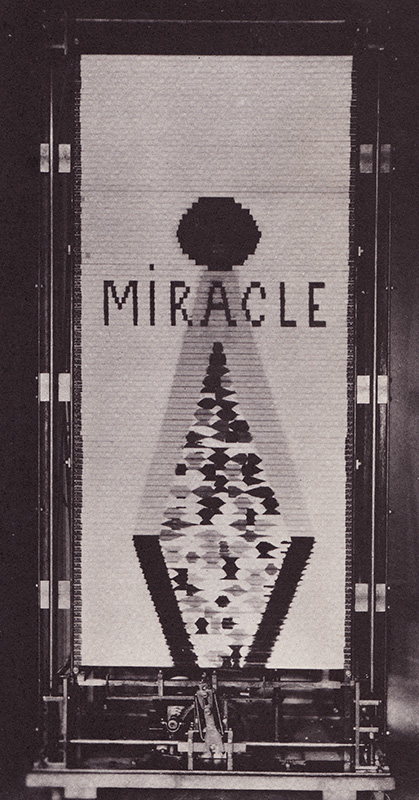

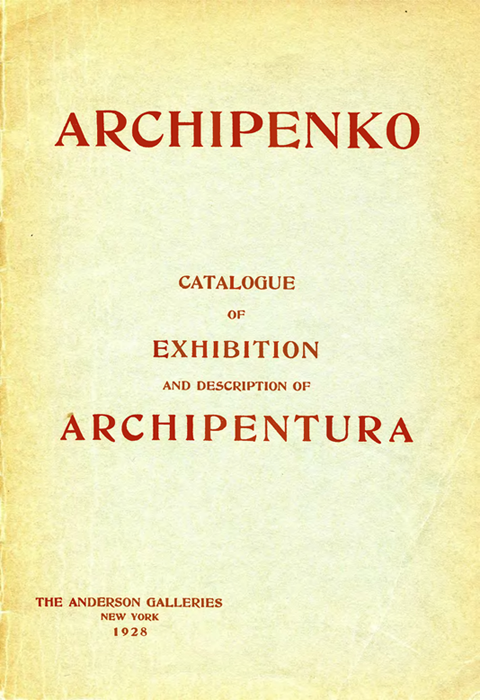

In Anderson Galleries in New York, Oleksandr Archipenko presented an innovation that you can see even today in the streets of any big city, though in a somewhat altered form.

“Archipeinture has nothing in common with the mechanical documentation of images in cinematography or other types of screen projections. This is the new meaning and new quality of painting created by an artist, directly complying only with his wishes and creative ideas.”

The picturesque method the artist called in his name, archipeinture, was a construct which moved a static image with the help of a clever mechanism (later patented by the author). Gallery visitors were hypnotized by the animated image of a girl who slowly undressing. We only know of this magical art object from photos since the original work has been lost while the invention has been realized in practical application. Billboards with rotating imagery in cities all over the world function according to the archipeinture principle developed by Alexander Archipenko.

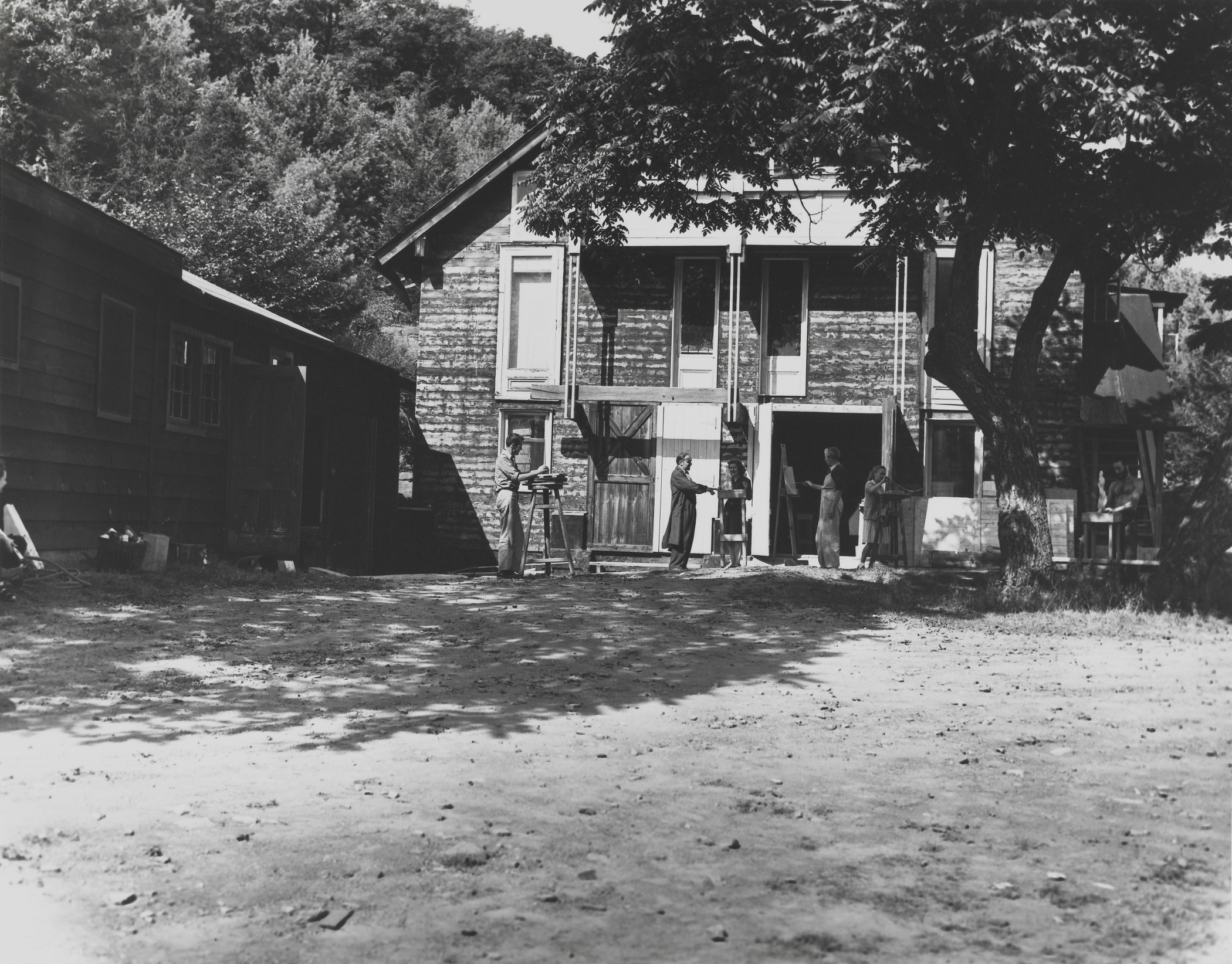

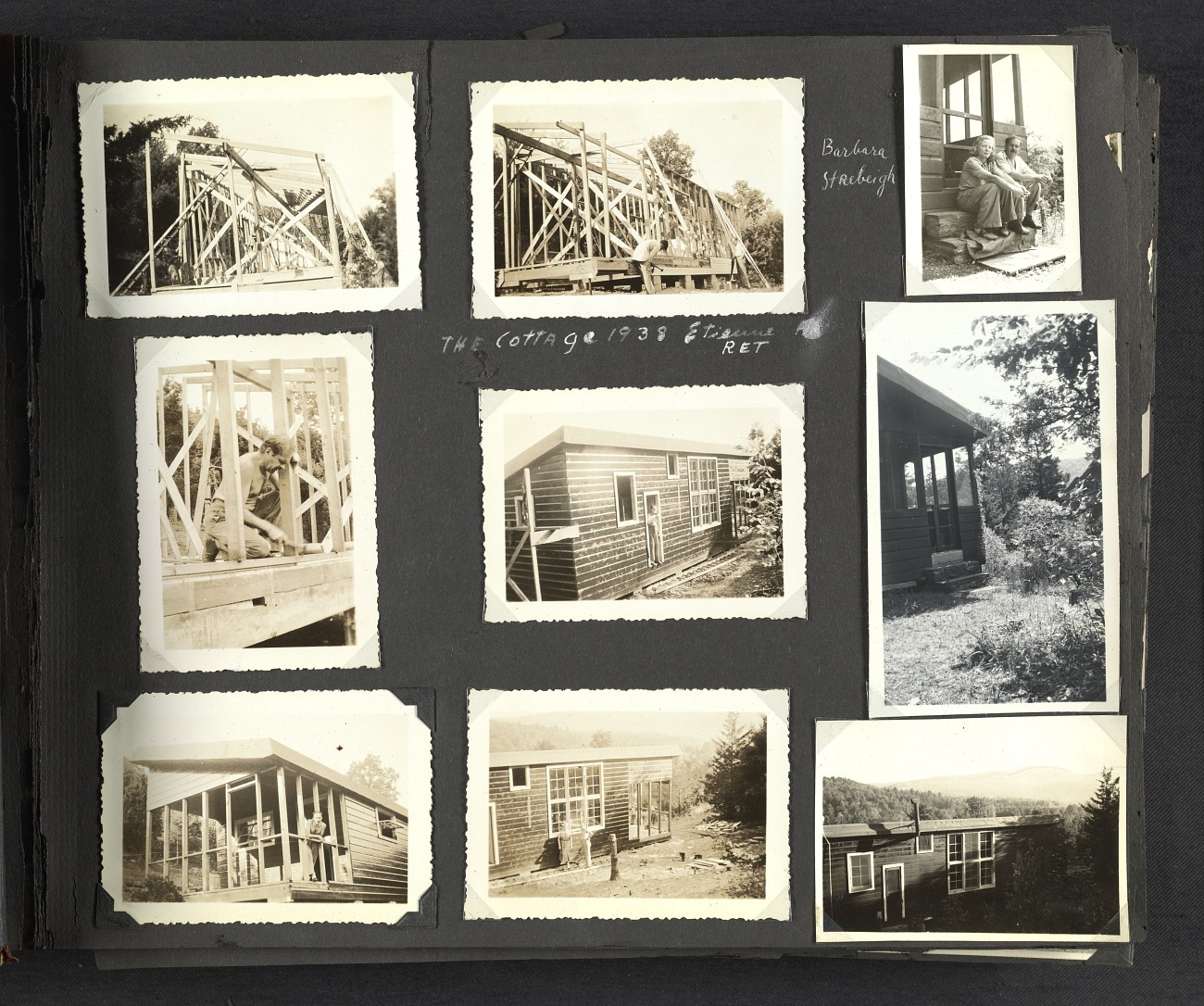

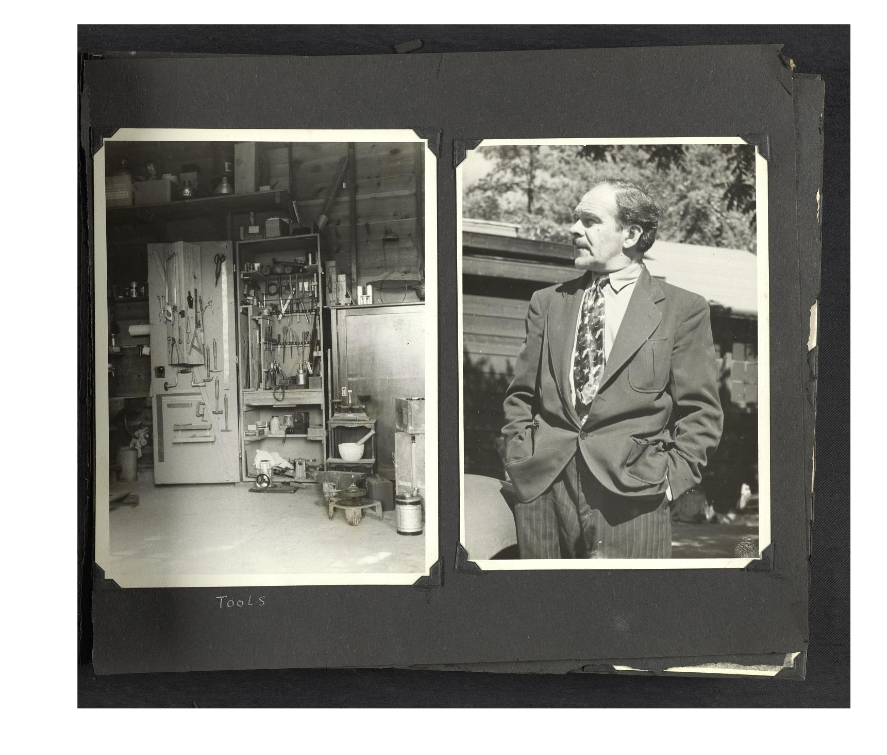

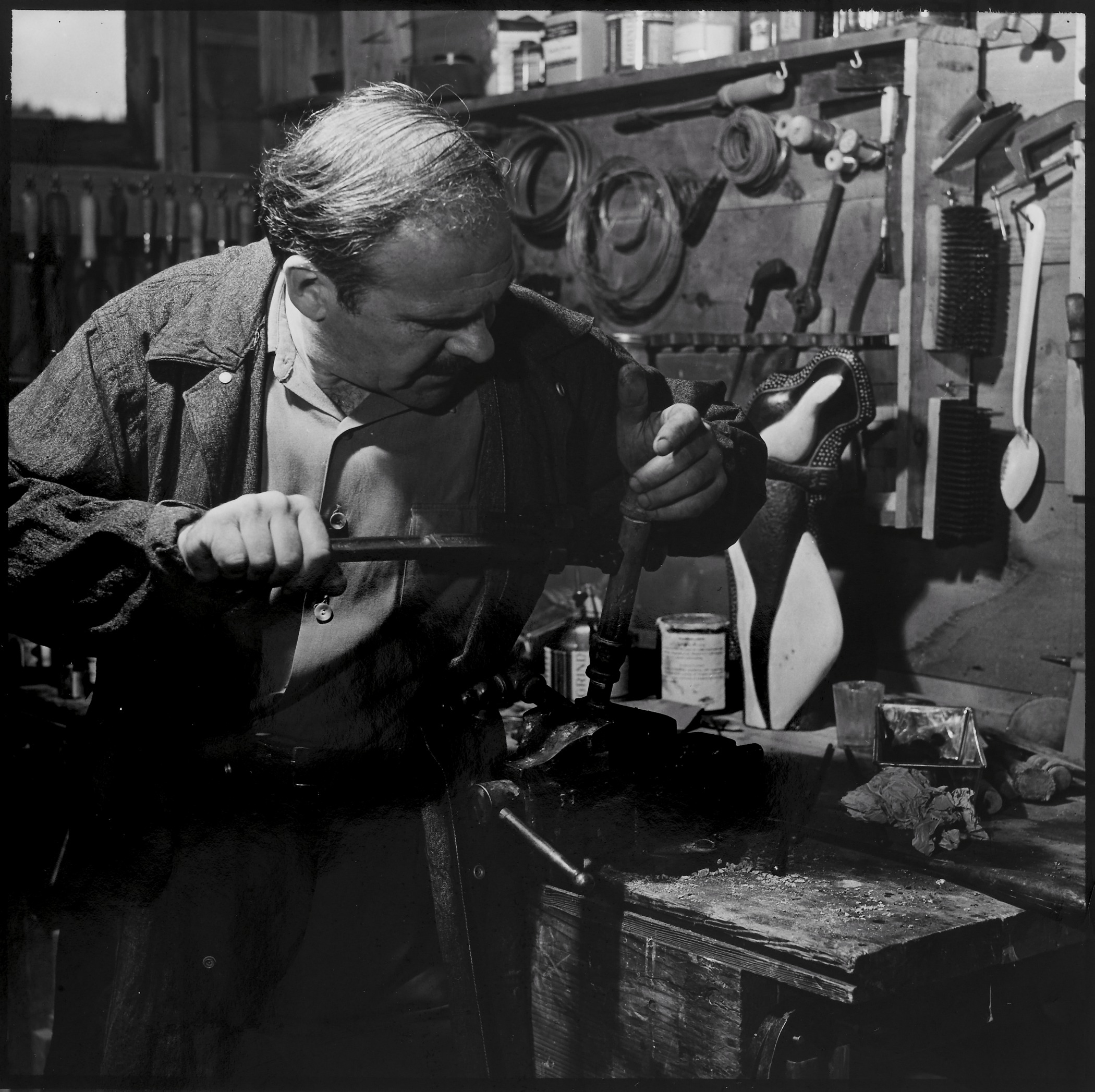

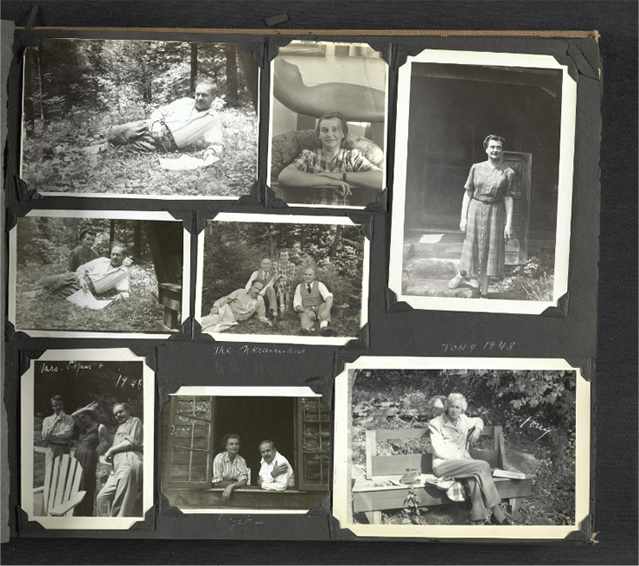

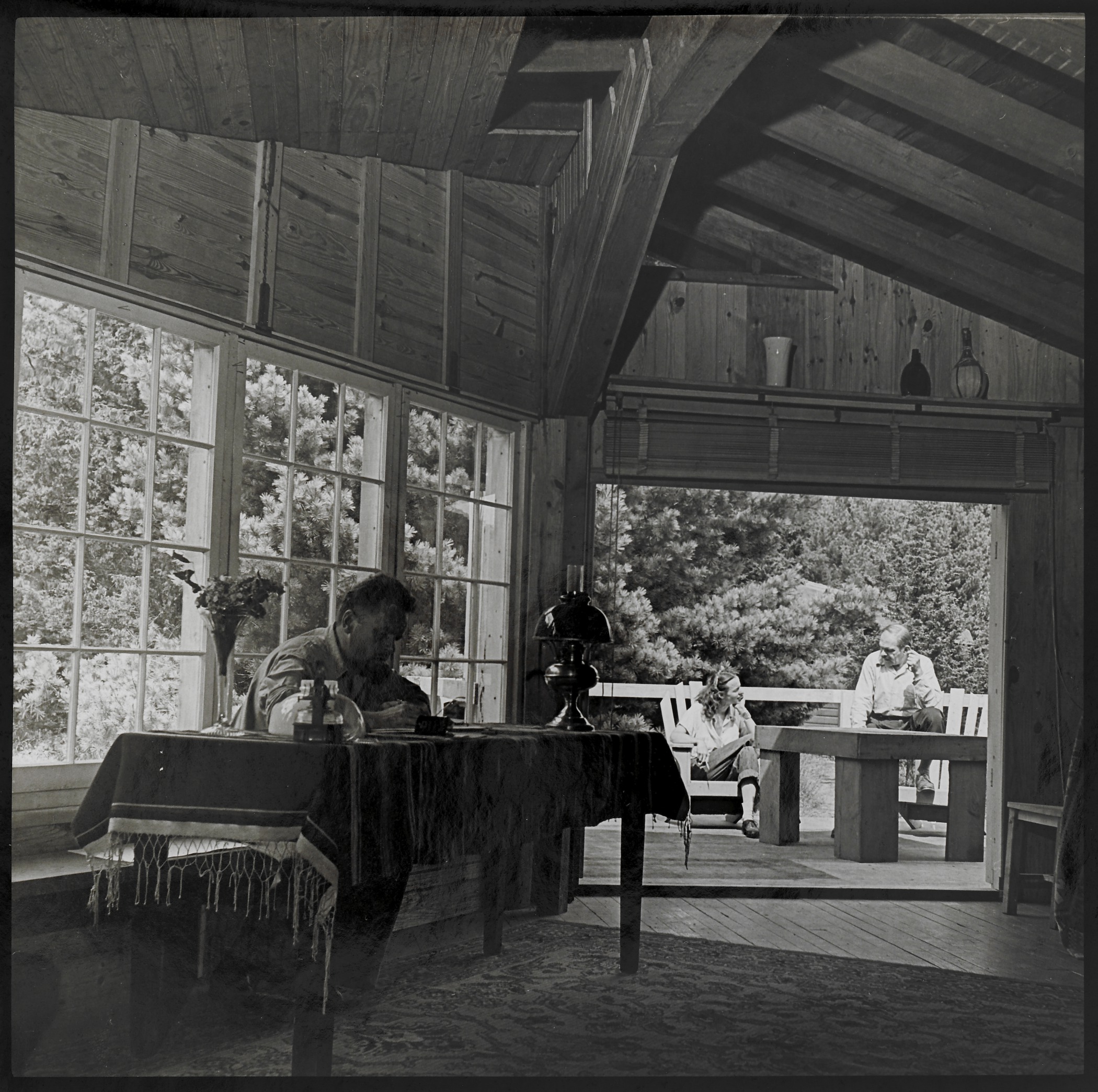

Bearsville, NY, USA

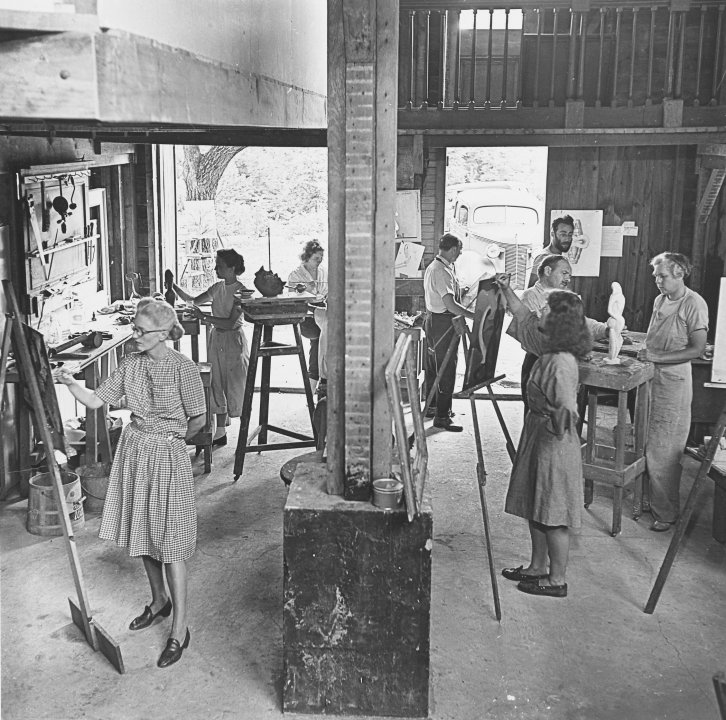

Oleksandr Archipenko designed and built a home for himself. He lived here for years with his first wife Angelica, with whom he had moved to the USA from Germany.

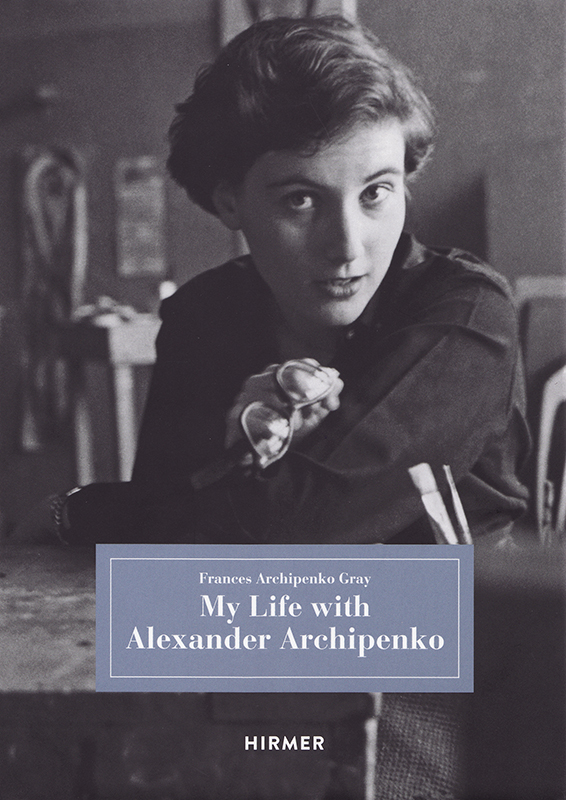

Spacious rooms, a big workshop attached where not just the author, but his numerous students could fit comfortably - very quickly this building transformed into a school, an iconic place to study avant-garde sculpture. Today the house hosts a foundation in his name, managed by Francis Archipenko Gray—Archipenko’s second wife, 49 years his junior and with whom had become acquainted at this very house.

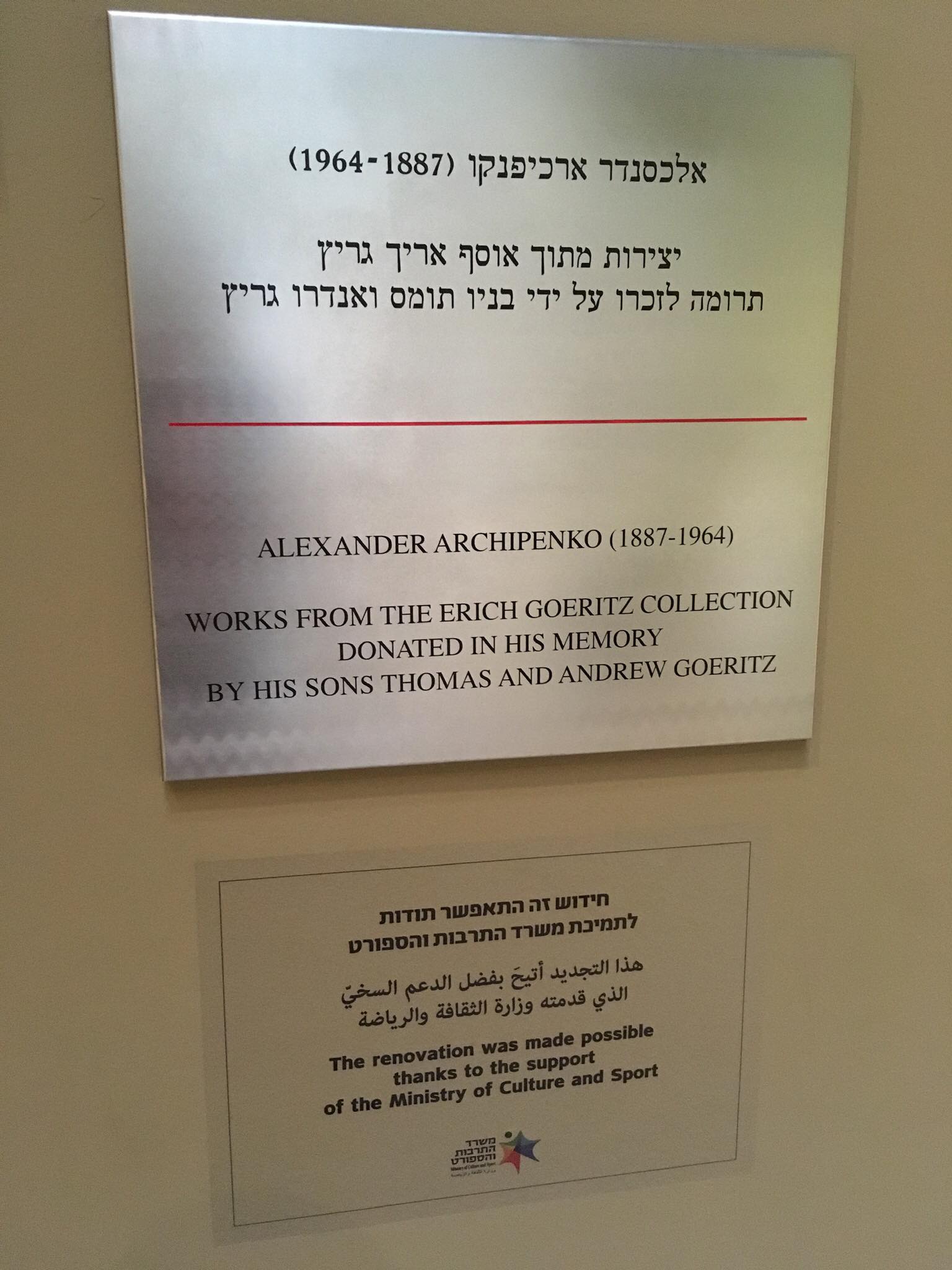

Sha'ul HaMelech Blvd 27, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel

Oleksandr Archipenkohad never been to Israel, but the Tel Aviv Art Museum houses the largest collection of his early work with 30 altogether. The work was purchased in Switzerland in 1929 by Leipzig-based textile factory owner Erich Greitz.

In 1933, Greitz (1889-1955), who was passionate about music and architecture, saw that Germany was undergoing a challenging period. The Third Reich became an existential threat to both his life and property. That year the prudent entrepreneur sent his entire art collection—including work by Alexander Archipenko, Oskar Kokoschka, Ernst Barlach, Erich Hekkel, Karl Smidt-Rottluff, Conrad Felixmuller, Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Paul Cesanne, and other artists—to a secure location. There they were overseen by Karl Schwartz, the first director of the Tel Aviv Art Museum. Prior to the rise of Nazi power in Germany, Schwartz had been the director of the Jewish Museum in Berlin. Archipenko’s Slavic origin and his avant-garde formalism left little chance that his work would survive in Nazi Germany, where all “degenerate art” would be destroyed. Greitz sent his collection for temporary storage at the Tel Aviv Museum, only to be donated officially to the museum following World War II. Later, other collectors also presented the museum with works by Archipenko. Archipenko would learn about the existence of the Tel Aviv collection of his work only in 1947.

38 Bedford Street, New York, NY, USA

In 1963, at his home at 38 Bedford Street in Greenwich Village in New York, with his young and loving wife at his side, Archipenko passed away. He was an artist who would determine the development of sculpture for the next century. In the last months of his life he worked on a unique cubist sculpture of King Solomon. Its model was made from white gypsum with black details defined by the artist and then cast in bronze. The artist who had worked with small forms all his life had concocted a project 18 meters tall. This idea––never fully realized in his lifetime––was truly grandiose. The generalized image of King Solomon would surely impress any viewer by a scale commensurate to that of the historical figure.

In 1975, his second wife Francis Archipenko Gray, personally supervised the casting of a four-meter sculpture which was installed in 1985 in the public space of Pennsylvania University in Philadelphia where it remains open for public viewing.