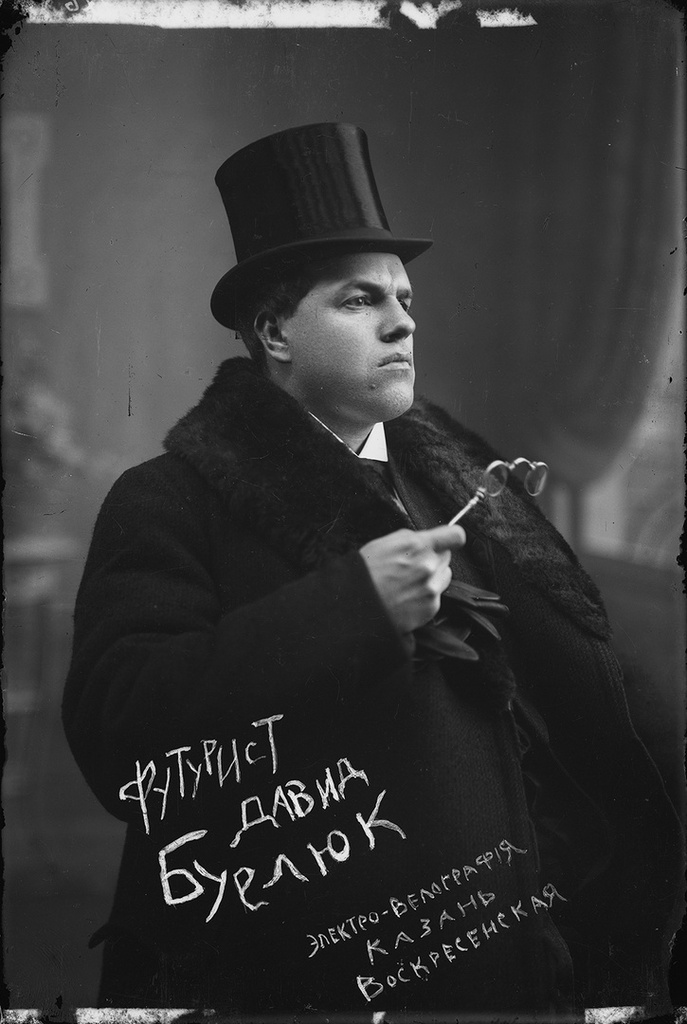

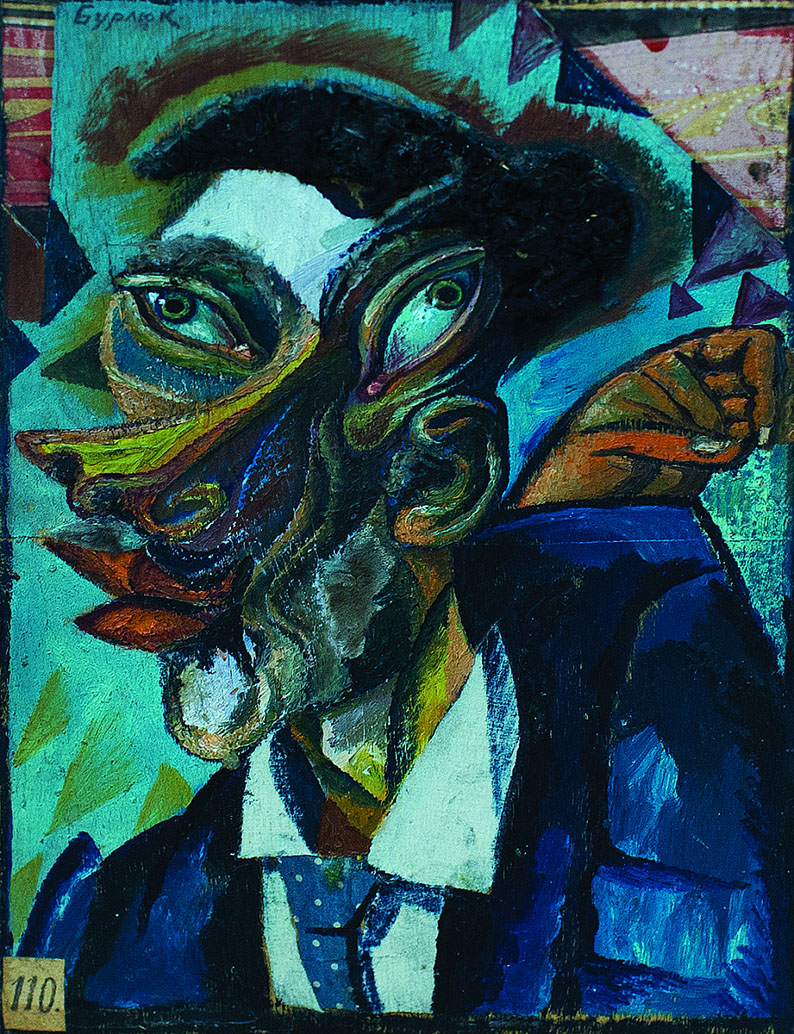

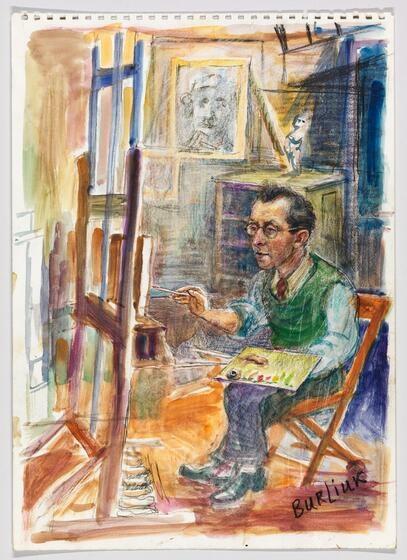

Burliuk David

David Burliuk is often called “the father of Russian futurism”, which means that Russian futurism had a Ukrainian father.

The scale of his personality defied all borders, both artistic and geographic. Burliuk was a futurist artist, a poet, an art theorist, a journalist, a cultural manager and a successful entrepreneur. His provocative activities energized artistic processes throughout the Russian Empire, from Odesa to Vladivostok. The Chornianka mansion in the south of Ukraine, where his father worked as a major-domo, saw almost every celebrity of Russian futurism in the 1910s – poets Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vasyl Kamensky, Velemir Khlebnikov, and Benedict Liefschitz. It was here that David Burliuk wrote the well-known manifesto of futurists – A Slap in the Face of Public Taste. “The big and tumultuous Burliuk breaks into life. He is wide and avid. He needs to learn it all, capture everything, eat everything up,” this is what Oleksiy Kruchonykh, a futurist poet, wrote about Burliuk.

In his lifetime, Burliuk managed to build a reputation in Japan and the USA and become a member of American Academy of Arts and Letters. Today, his work is included in the collections in the biggest museums of the world: MOMA, Whitney, Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum Madrid, and many others.

University Embankment, 17, St Petersburg, Russia, 199034

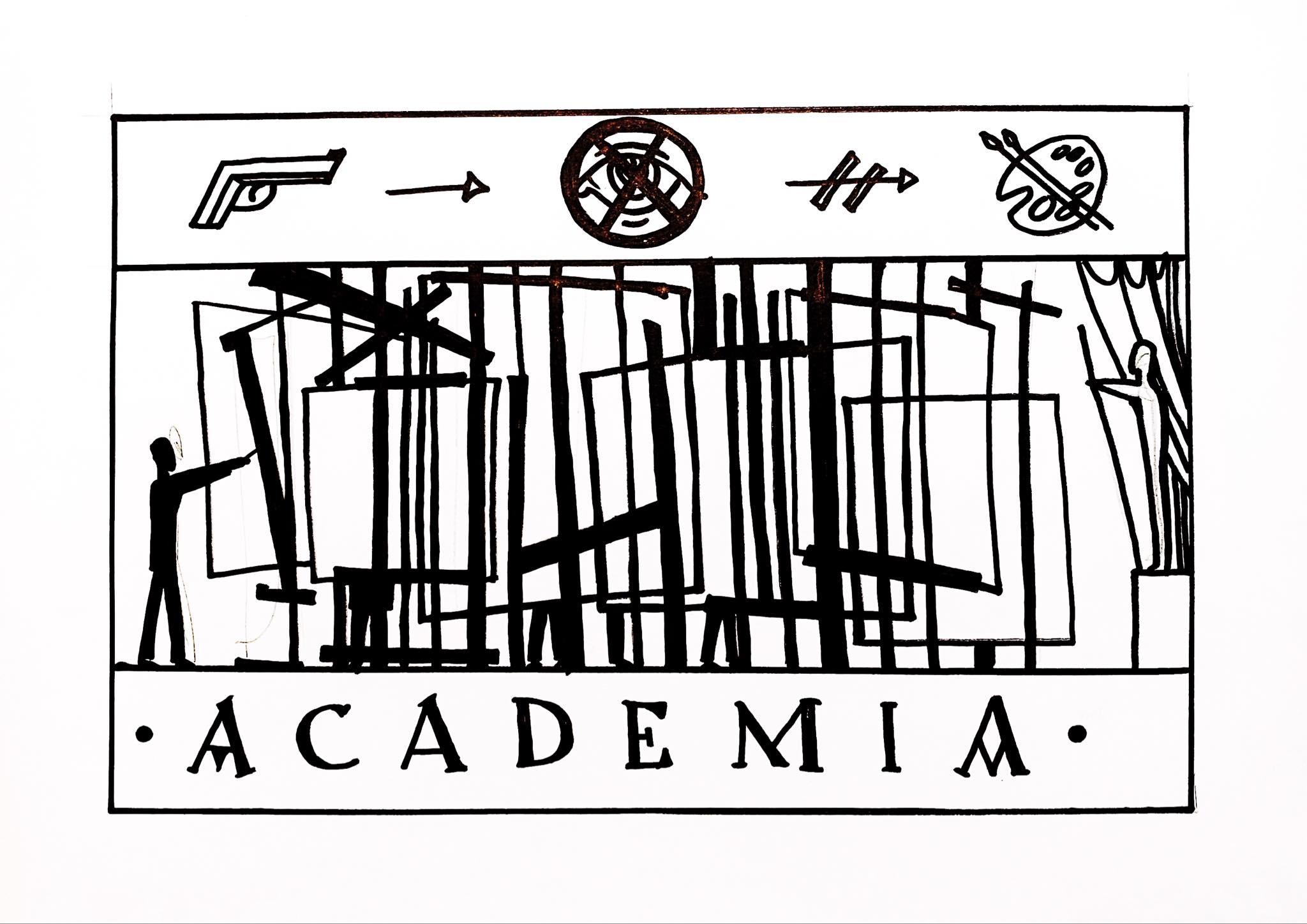

In 1902, David Burliuk and his sister Lyudmila went to Saint Petersburg to apply to the Academy of Arts. However, David had a stroke of bad luck – during the exam, he was assigned a spot in the very back of the room from where he could hardly see the model out of his only functioning eye. The head of the jury at the time was Ilya Repin, a well-known Russian artist. He remarked on Burliuk’s talent but did not admit him and only laughed at the dream of the one-eyed youth who wanted to become an artist.

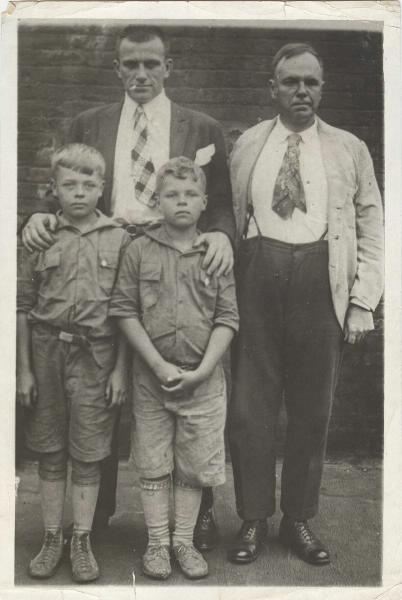

Burliuk had lost an eye in his childhood. The accident happened at the Burliuk family mansion, perched high on a hill above the pond on the Semyrotivka farm in the Lebedyn district of the Kharkiv region. Burliuk lived here until 11 years of age. The boy shot himself while playing with a toy pistol, and despite his family’s efforts to treat him at home—for over a year—the eye could not be saved.

It was only later that his glass eye would become a part of Burliuk the futurist’s provocative image. Initially, the injury only created problems which put his creative dreams into doubt.

Georgenstraße 16, 80799 München, Germany

In the depths of the yard a 16 Georgenstrasse, among tall trees, a new high-rise hides. Prior to the Allied Forces bombings in 1944, Anton Azbe’s private art school where Burliuk studied from 1903-04, had been located here. The school had a peculiar appearance. It was a wooden house built in quasi-Russian style with roosters and carved towels, which stuck out like a sore thumb in this respectable Munich neighbourhood.

For Burliuk, it was already the second attempt to study abroad. In the autumn of 1902 he had been accepted at the Munich Academy, by the workshop of Professor Wilhelm von Diez but only lasted at the school for several months.

The ambience of private school was more to Burliuk’s liking. Azbe attended the school almost every day and held classes with the students. He paid special attention to their individual talents and helped discover their own creative styles. “Azbe admired me,” Burliuk said, “and when he showed my work to all students he called me ‘a beautiful wild horse from the steppes’.”

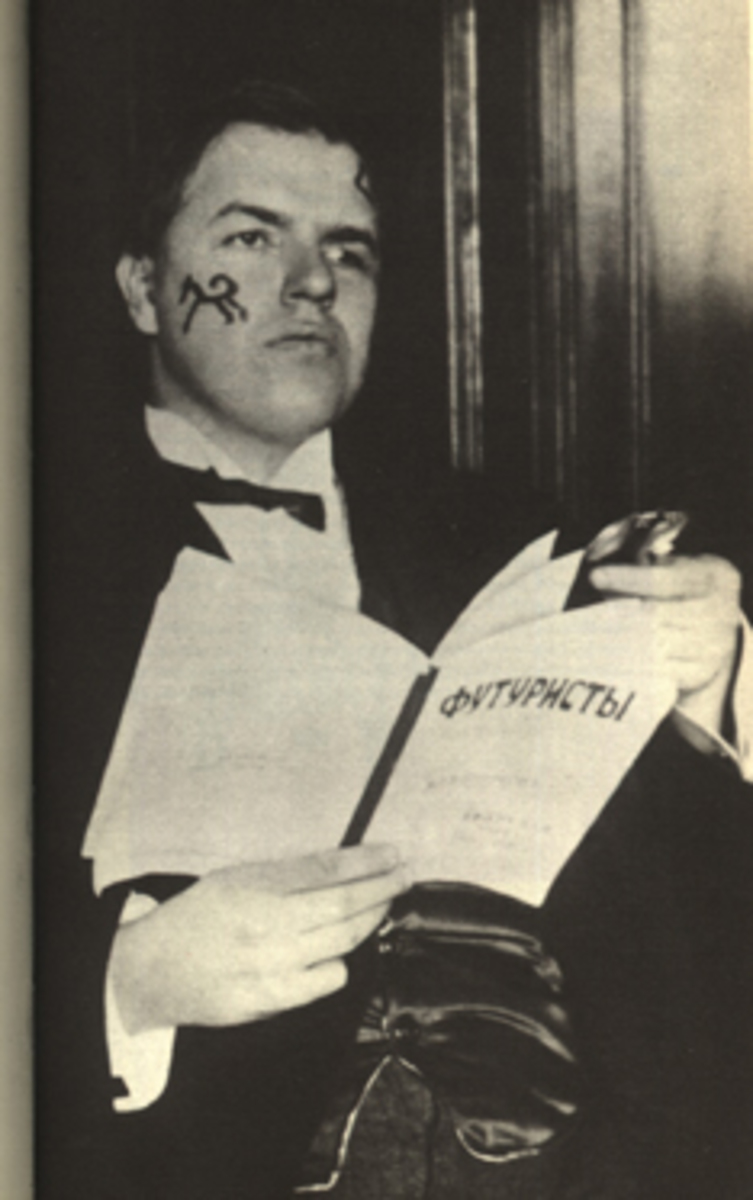

This image stuck to the artist for a long time. Later he started painting horse images on his face, in this way starting his first body art experiments even before it was established as a form of avant-garde art. And the image of wild horseman, a Scythian warrior, became a metaphor of “Russian futurism” in general. This wasn’t by chance: the headquarters of Gilea, the first literary and art group organized by Burliuk, was that same mansion in Chornianka (Kherson region) where his father worked. (The house where the Burliuk family lived was torn down in the early 1980s with only a shed and the old school building remaining). The name of the association, Gilea, was lifted from Herodotus’s History the name the ancient historian gave to the region of Scythia near the Dnipro where the mansion was located.

10 Rue Constance, 75018 Paris, France

In 1882, at 10 rue Constance in Paris, Fernand Cormon’s atelier opened shop, quickly becoming a popular spot for informal art education. Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec also studied there at the time. Cormon, rather free with who he admitted to his school, traditionally had large numbers of students from Eastern Europe. He held no entrance exams, knowledge of French was not required – it was enough to show several works. In spring 1904, David Burliuk also joined the studio.

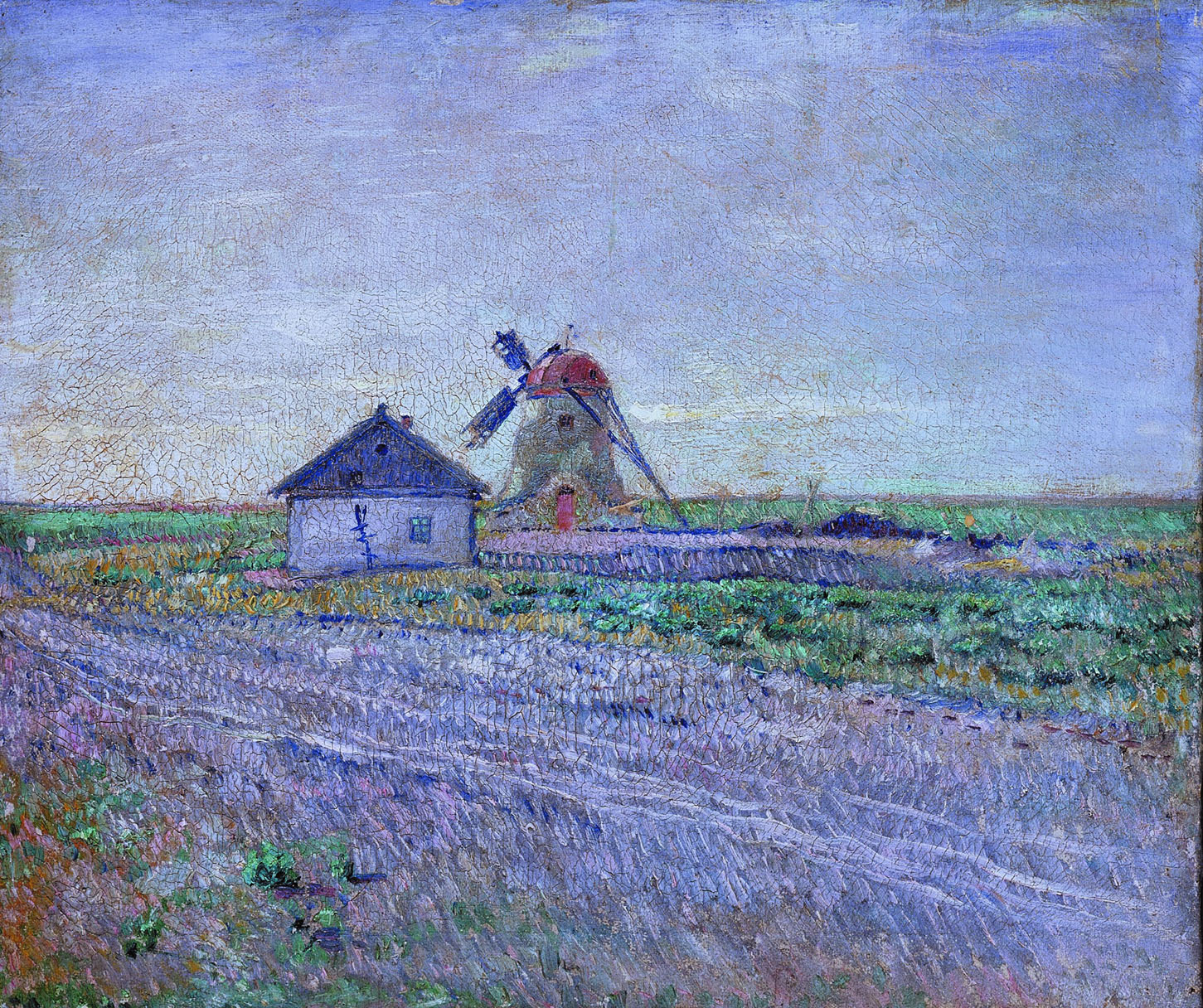

Paris attracted the artist not so much because of the easy access to education but more for the chance to join in on this tumultuous artistic environment and see the works of distinguished French artists. Burliuk studied both the glorified collections of old masters and the centres of new art. “1904 in Paris for me was the year of Courbet and Maurice Denis,” the artist wrote in his memoir. “Courbet had a huge influence on me. I admired the coldness of David, but my imperfect sight always lured me towards more picturesque self-expression.”

However, in July 1904, due to the outbreak of the Russian-Japanese war, David Burliuk returned to the Russian Empire.

Myasnitskaya Street, 24, Moscow, Russia

At the close of 1907, brothers and artists David and Vladimir Burliuk organized an exhibition at Stroganov College of the Stefanos group which also included Aleksandra Exter, Mikhail Larionov and Aristarkh Lentulov. The Burliuk brothers had become close to “leftist” artists at that time (this is how radical art innovators were called then) and started actively promoting the idea of new art. The exhibition was financed by the artists themselves. Burliuk’s father allocated 500 roubles. After Moscow, the exhibition departed for Kyiv, then Kherson and Petersburg.

Avant-garde artist Alexandra Exter was responsible for a new art exhibition in Kyiv (with core works again from the Burliuk brothers, Exter, Larionov, Lentulov, and several others) which she personally arranged with the Kyiv governor. The Link exhibition opened on 2 November 1908 in J. Jindrisik’s music instrument store at 58 Khreschatyk street. Later, Burliuk would regret that they did not employ the store owner’s avant-garde sounding last name for the exhibition.

Until then, no other exhibition had had such a scandalous reception. Critics wrote about Link, calling it an exhibition of “talentless artists” and “a terrible, savage phenomenon”. The reviews and feedback were published by all the municipal dailies. The press even included several caustic caricatures. The Burliuk brothers got it the worst, even though they had yet to begin their radical art experiments and were only starting to master impressionism and post-impressionism.

The last group performance took place in the spring of 1910 in Petersburg at the Triangle-Wreath-Stefanos exhibition. Following this, the group disbanded.

Myasnitskaya Street, 21, Moscow, Russia

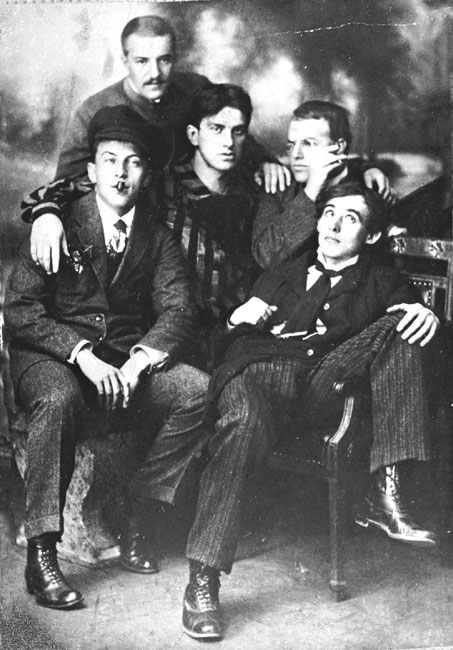

In the autumn of 1911, David Burliuk entered the Moscow College of Art, Sculpture and Architecture where he met young Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky.

“Burliuk appeared at the college. Arrogant airs. A glass eye. A frock coat. Walking around singing under his breath. I started to harass him. We nearly fought” is how Vladimir Mayakovsky describes Burliuk’s arrival. Burliuk also singled out Mayakovsky from the rest of the students: “Some uncombed and unwashed big guy with a handsome Apache face persecutes me with his jokes and hints, calling me a ‘cubist’. It has got so bad I was ready for a fist fight but… we made peace, and not just that – we became friends.”

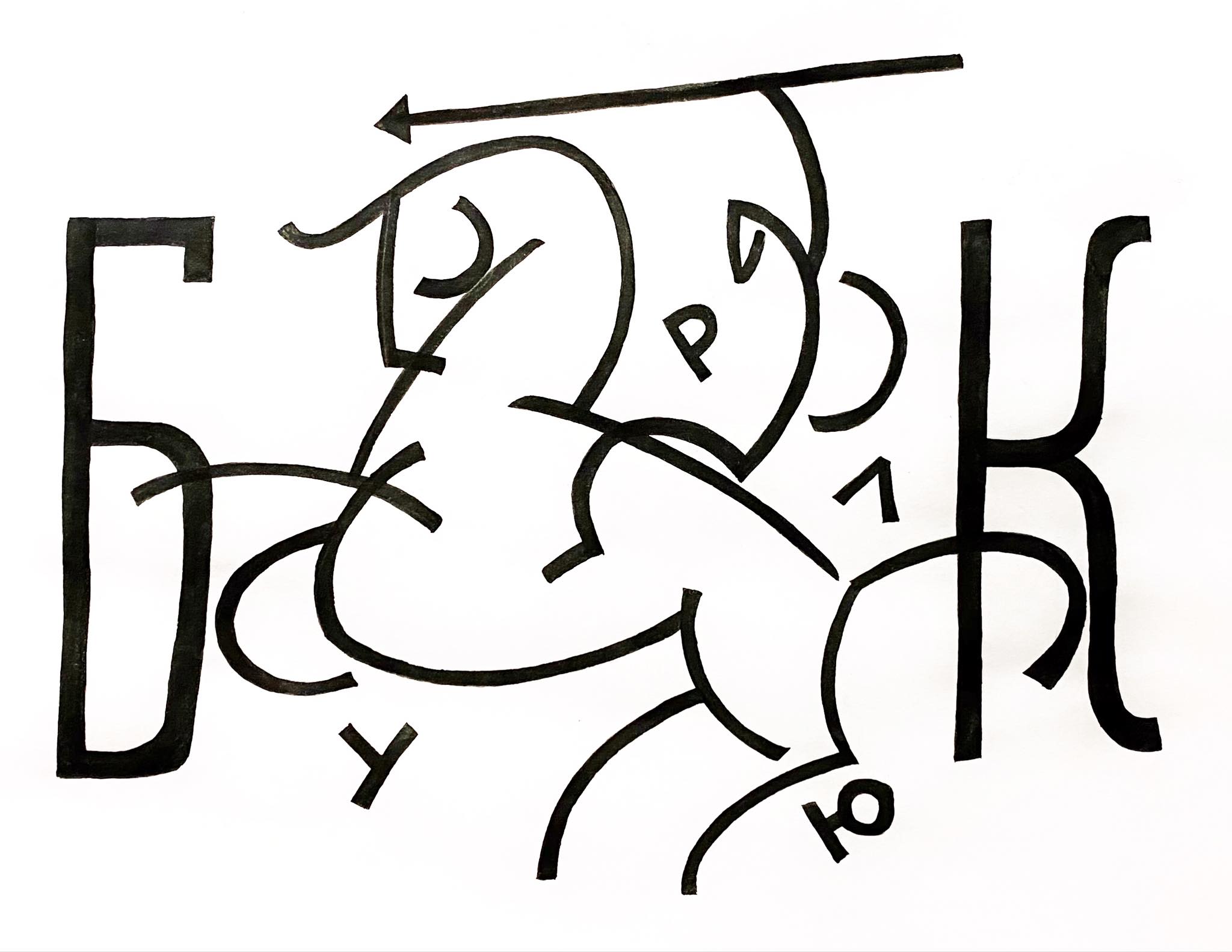

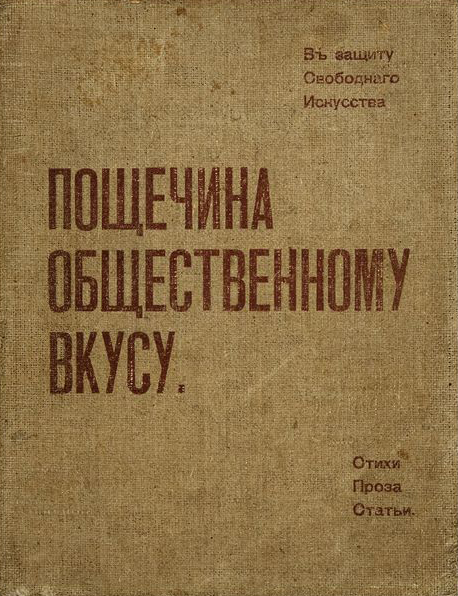

Burliuk immediately saw the poetic talent in Mayakovsky and talking about him everywhere as a “famous ingenious poet” even loaning him money for food so that he could keep writing. Believing in his own talent, Mayakovsky quickly transformed into a celebrity of Burliuk’s poetic circle and became an active participant of the Gilea group. Together, they prepared the A Slap in the Face of Public Taste collection (1912) in which they promised to throw the classical authors off the ship of modernity and establish new poetic principles founded on self-sufficient creative practice.

The propaganda from Burliuk and Mayakovsky irritated the college administration, and on February 21, 1914 the council of teachers unanimously expelled both.

Vozdvizhenka Street, 10, Moscow, Russia

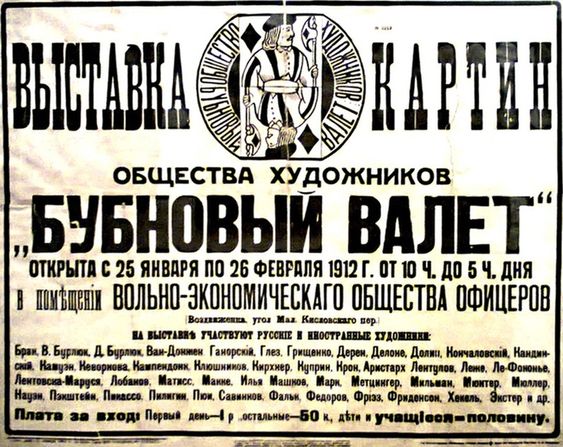

In January 1912 in Moscow, a notorious exhibition by Jack of Diamonds opened on the premises of the Officers Economic Association. Participants of the exhibit rejected academism and realism. Burliuk had been preparing thoroughly for the show during his Christmas vacation of 1911. Among the other organizers were Pyotr Konchalovky, Ilya Mashkov, and Aristarkh Lentulov.

The exhibition spurred huge public interest. To explain the principles and methods of leftist art to the public, on 12 February, Jack of Diamonds organized a lecture with discussion in the Big Room of the Polytechnic Museum. Reports were presented by Kandinsky, Burliuk, and Kulbin. Here was some expectation among the public of a clash between Jack of Diamonds and Donkey’s Tail, and this expectation was rewarded. Natalia Goncharova appeared onstage and condemned the activities of Jack of Diamonds in an exalted manner; for their bowing down to Western art and excessive theorizing in place of creative practice. This episode laid the foundation for lasting dissent between the two groups and lending an odour of scandal to the names of the new art propagandists.

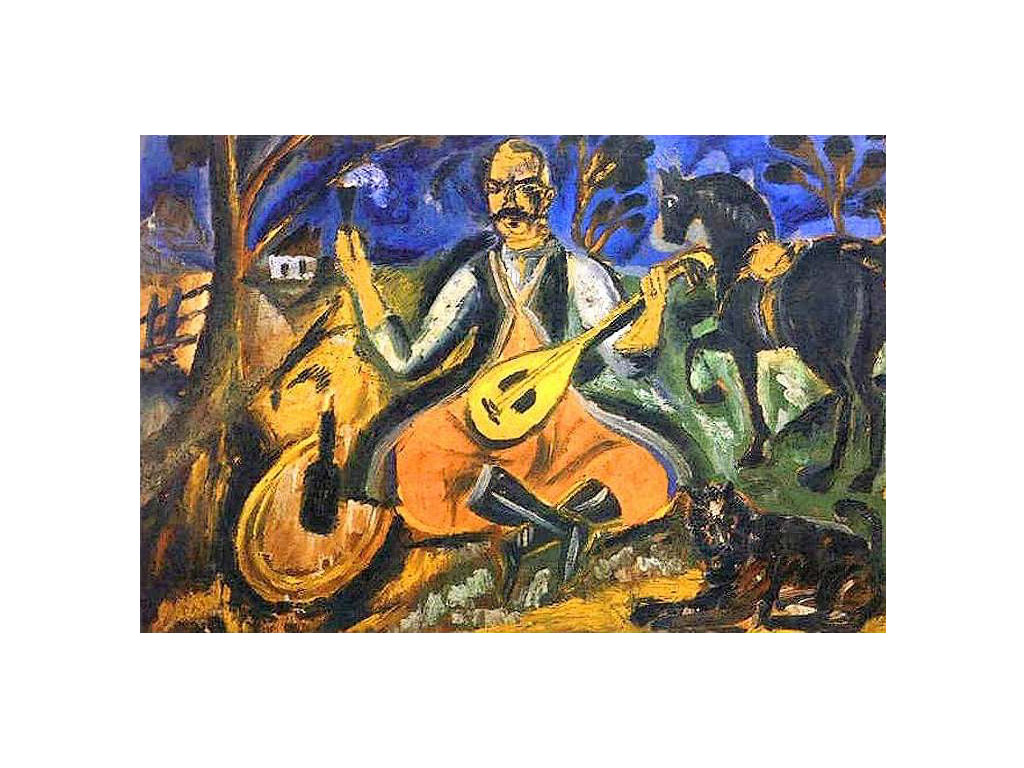

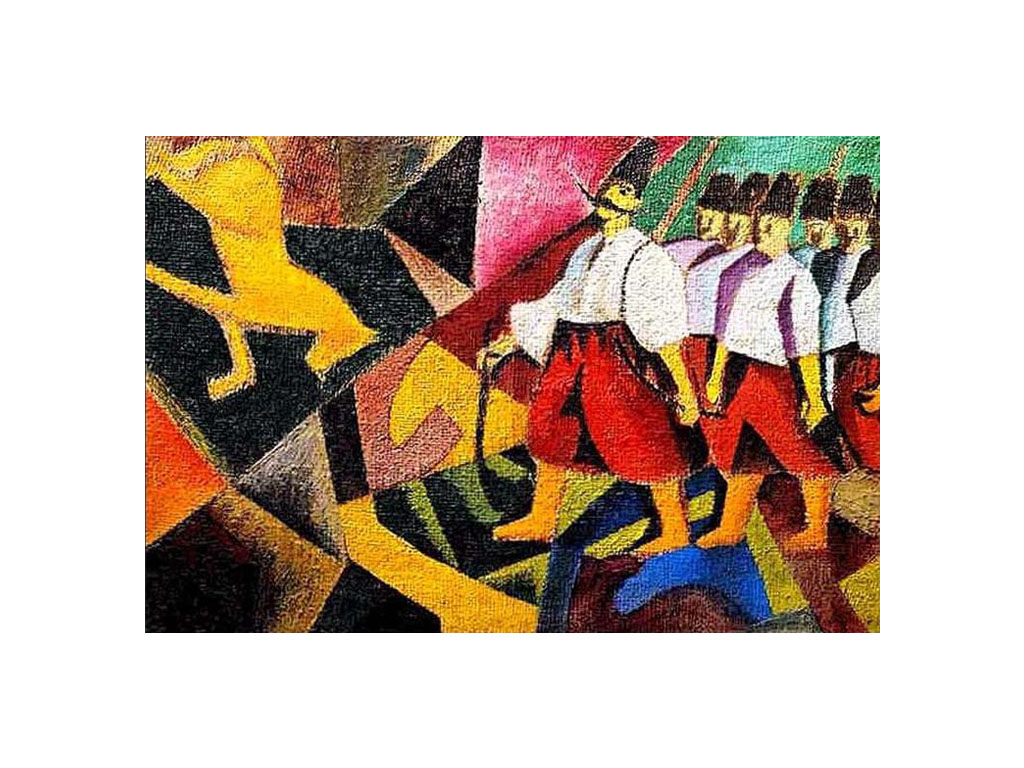

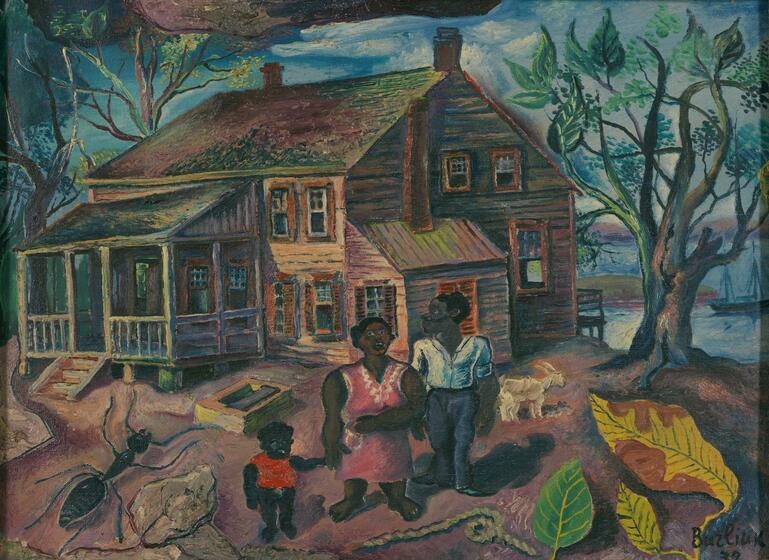

As for Burliuk, leftist artists criticized him for the vivid Ukrainian themes in his work and the way it diluted the generally accepted cosmopolitism of the movement. Kazimir Malevich said about his compatriot that he was lagging behind the times with his ancient Malorossiya (the diminutive moniker for Ukraine during the Russian Empire). However, David Burliuk stubbornly kept painting numerous Mamays (Cossack Mamay, 1912) and Zaporizhzhya Cossacks raids (Ukrainians, 1912), showcasing the connection with the Cossack past of his ancestors.

Mykhaila Hrushevskoho Street, 3, Kyiv, Ukraine

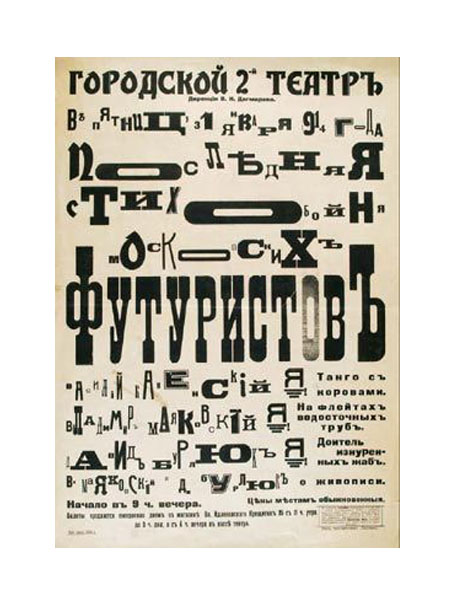

On 31 January 1914 in the Chateau-des-Fleurs theatre (now the site of Kyiv’ Dynamo Stadium) a performance of the Gilea group was held, with the participation of David Burliuk, Vasyl Kamensky and Vladimir Mayakovsky.

In December 1913, the trio set out on a Futurist Tour and visited 16 cities throughout the empire over four months. The reputation of the futurists had reached the provinces and during their tour most of the audience attended the events expecting a scandal. Such expectations were encouraged by the artists themselves. For example, a Gilea performance in Kyiv was advertised on posters as “The Last Poetry Fight of the Moscow Futurists”. The public saw a grand piano hung over the stage upside down. “The grand piano is hanging because I am not going to play it,” Mayakovsky boomed, outvoicing the shouts from the audience.

The Gilea group actively played on the public’s perception of art hooligans – they walked the streets wearing multi-coloured clothing and with painted faces, making shocking statements and exhibiting provocative behaviour. All this worked counter to the artists’ ambitions of being heard: “People come to see ‘real’ futurists with the same expectations and moods as they would go to see savages. They don’t come to listen to futurists, they come to watch them.” (Trudova Gazeta newspaper, Mykolayiv)

Karla Libknekhta Street, 42, Yekaterinburg, Russia

In December 1918, as part of their Siberian tour, David Burliuk came with his exhibition to Yekaterinburg. An hour after his arrival in the city he found the premises for the exhibition and concert, submitted an article about futurism to the local paper and started hanging paintings. The following day, at 10 a.m., the exhibition started in the School of Art and Industry. Meanwhile, Burliuk was walking around the city in his motley vest, luring in a crowd. At lunchtime he arrived at the exhibition accompanied by a rowdy horde.

This scene was repeated from one city to the next. The tour on which David Burliuk went in the heat of civil war (from April 1918 until June 1919) seemed a risky affair. Finding himself in the provinces in 1918, and cut off from the artistic life of the capital, with a wife, two small children and no means of subsistence, Burliuk chose touring as the only way to earn money and establish himself as the leader of the avant-garde movement.

His route was determined by the “road of life” for many thousands of refugees—the Trans-Siberian railroad. The artist visited Zlatoust, Satka, Mias, Ufa, Yekaterinburg, Omsk, Tomsk, Chelyabinsk, Irkutsk, Chita, and Khabarovsk.

Burliuk knew how to charm an audience and his paintings sold well. The artist created new paintings for sale while on the road. He did take the effort too seriously and was able to sell copies of his Portrait of my Uncle in almost every city he visited. He produced the painting quickly in the hotel, gluing pieces of newspaper on a face he’d torn into pieces and having three eyes and two noses. Despite the civil war, the popularity of Burliuk’s performances and exhibitions was so great that he did not just manage to support himself and his family but also ensured a decent life for the poets and artists who accompanied him.

7 Chome-22-17 Nishigotanda, Shinagawa City, Tokyo 141-0031, Japan

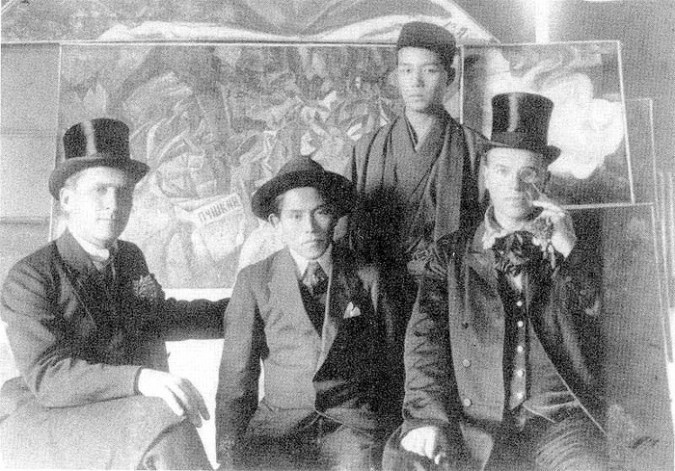

On 29 September 1920, David Burliuk and Viktor Palmov, a Ukrainian artist of Russian origin, set out for Japan, travelling first to Tokyo where the local artistic community was looking forward to meeting “the father of Russian futurism”. There was no better time to visit Japan: the country had just become interested in innovative art trends, a group of futurist artists had formed, and the arrival of Burliuk loaded with 400 paintings of different avant-garde directions was perceived as an event on a globalscale.

Burliuk immediately dug into preparing an exhibition. Its opening took place less than two weeks later, on 13 October, at the premises of the Hoshi-Seyak Pharmaceutical Company (although the company still exists, it is unknown where the company premises were located in the 1920s). The exhibition announcements appeared on the front pages of the most important Japanese newspapers. All of them wrote about Burliuk with respect and not with the irony he had gotten used to in Russia. Colleagues respected him, and the members of the emperor’s family bought his works.

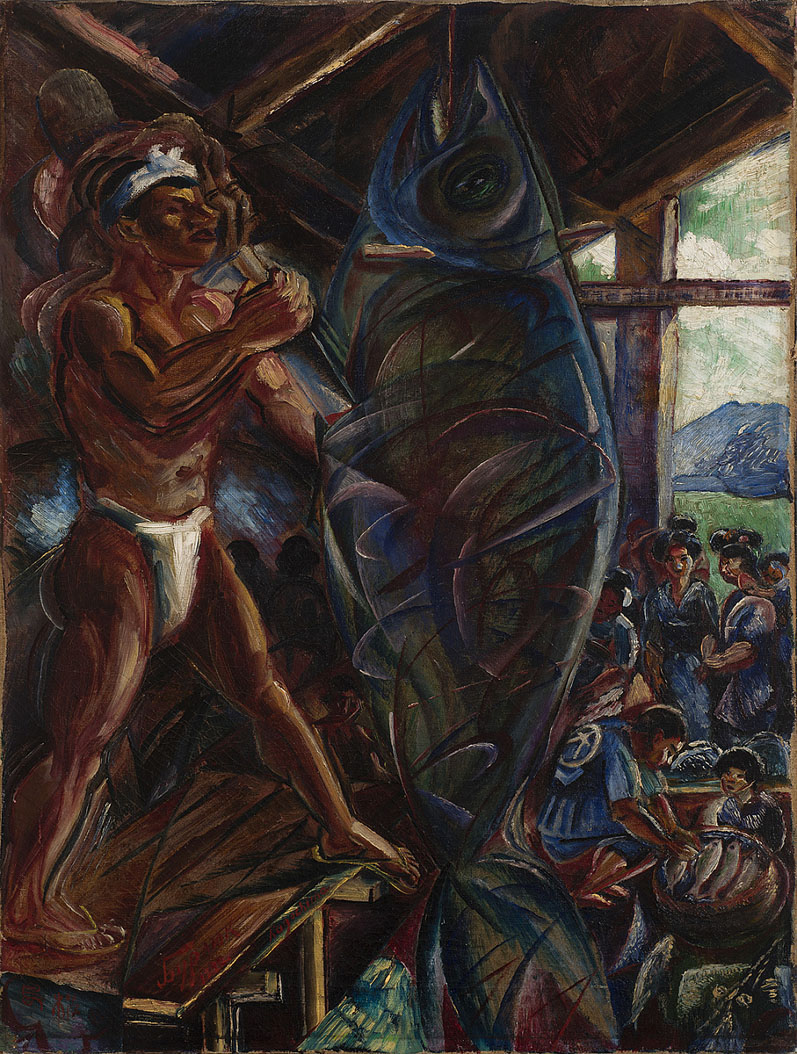

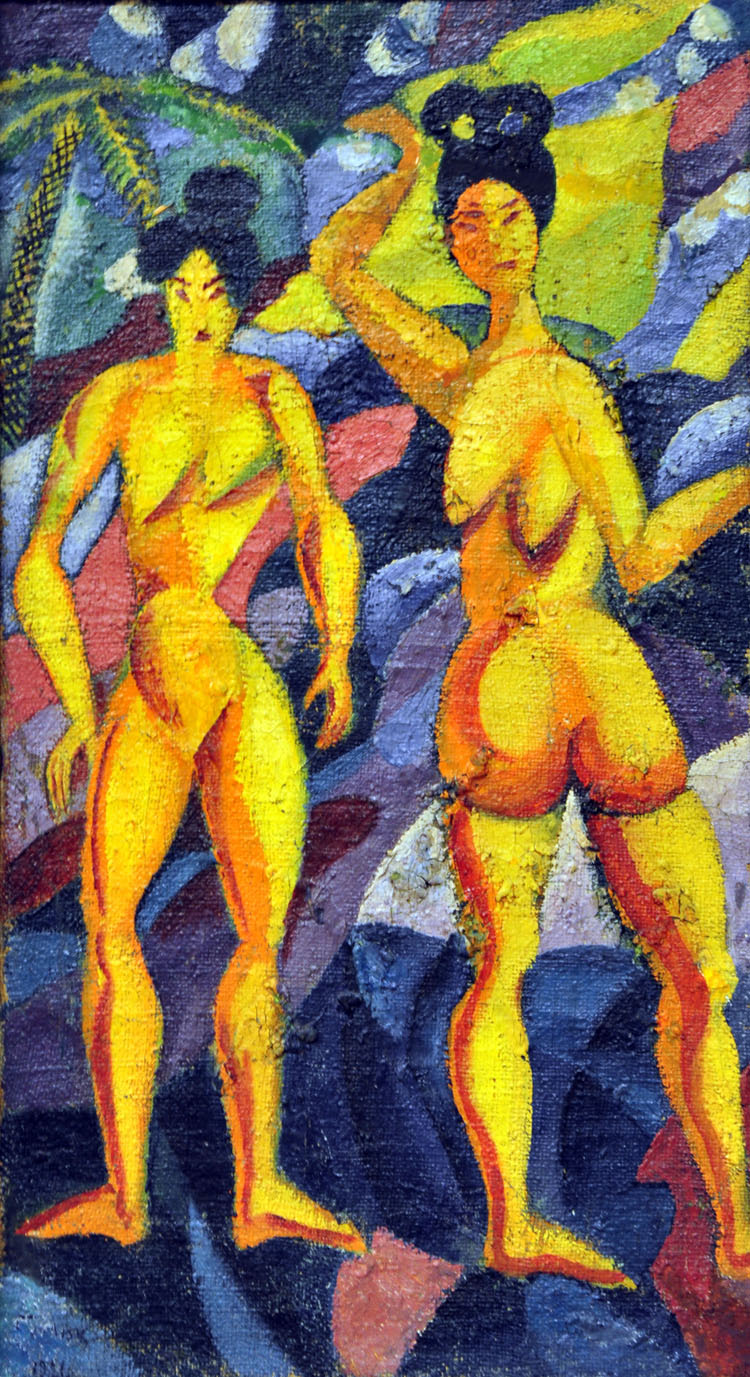

Two years later, Burliuk organized exhibitions in Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto and Yokohama. From the second exhibition, he began showcasing paintings produced in Japan under the influence of “oriental” art. Japanese art techniques occupied an organic place in the artist’s campaigns. At one of his lectures at Tokyo university, Burliuk suddenly threw ink from the pot on a piece of paper attached to the wall, demonstrating the “leaking colouring” technique. In his works, he combined decorative principles of Japanese art and futuristic techniques conveying movement (like in Japanese Woman Sowing Rice and Japanese Man Cutting Tuna). He experienced a creative outpouring there and produced over 300 paintings, half of which were purchased by Japanese collectors.

Japan, Tokyo, Ogasawara, Chichijima, 父島

While in Japan, David Burliuk did not lose a single opportunity to see the remoter parts of non-Europeanized Japan. On 1 November 1920, after the closing of his Tokyo exhibition, the artist set out for Oshima Island. He was amazed by everything: hotel rooms without windows and doors you can get into from all four sides, unusual cookies of bright green colour, clothing. He is interested in furo, Japanese sauna, and wants to treat the rheumatism he had suffered from since his stint in Siberia.

Burliuk had his wife and children join him in Japan and together they spent the winter of 1921 on Titijima island. This was truly an exotic experience. “Just imagine! Living on a small island, among infinite waves, living on a rock where a ship comes only once a month,” he wrote with excitement. Titijima was to Burliuk what Tahiti was to Gauguin. The locals were not too shy to pose for the artist, even naked. In four months on the island, Burliuk created lots of portraits and landscapes combining futurism and traditional Japanese art.

Naturally, Burliuk could not leave Japan without conquering Fujiyama first. They ascended it as a company of three people: David; Vaclav Fiala, an artist and the husband of his sister Marianna, and Herbert Peacock, an Englishman and old friend of Burliuk’s. They reached the peak on August 1, 1921. It was sunny so Burliuk was able to make several sketches. “You catch the hem of heaven like a nail sticking out from the ground,” the artist wrote. Burliuk saw Fuji for the last time from Yokohama before sailing off to the States.

2116 Harrison Avenue, The Bronx, NY, USA

On 2 September 1922, the family of David Burliuk arrived in New York. The house where the Burliuk family rented their first American apartment, and where he would be visited several times by well-known Russian futurist poet and friend Vladimir Mayakovsky during his American tour in 1925, has not survived. At the time, Burliuk met the poet almost every day, organized his performances and publications in the media, and on 9 August David and his wife Marusia organized a lunch in their apartment to introduce Mayakovsky to the young poets of New York.

Marusia often wrote in her diary about their household, which looked rather modest: “Our life seems poor to everyone who visits”. “Burliuk has no soft chairs, linen or table silver,” Mayakovsky remembered.

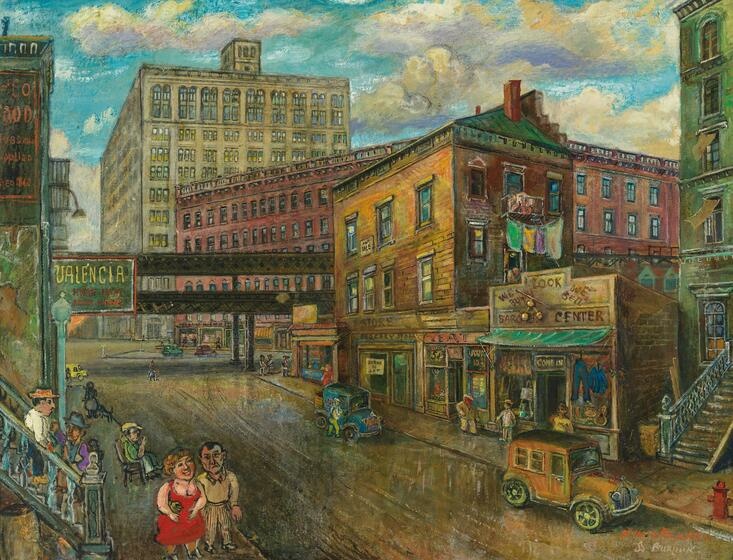

Burliuk’s life in America did not start out on a high note as it had so often before. He was practically unknown in this part of the world, so the artist had to create his reputation from scratch to prove that he was not a simple immigrant. This is where the self-aggrandizing self-proclamation of “the ingenious artist Burliuk” arises. It was his common practice—to write and speak about himself in the third person. And before this self-branding would bear fruit, Burliuk went to work in a pro-Soviet newspaper, Russky Golos, where he stayed for 17 years. Burliuk was responsible for its literary page, published and commented on short stories and poems by Russian authors living in the States as well as his own poems and stories and informed the public about literary life in Russia.

105 E 10th St, New York, NY 10003, USA

In 1929, the Burliuk family moved to Manhattan. There are several addresses indicated in the artist’s correspondence as they moved rather often, but always on the same street. High rent prices and lack of heating in winter were persistent problems that forced the family into semi-nomadic lifestyle.

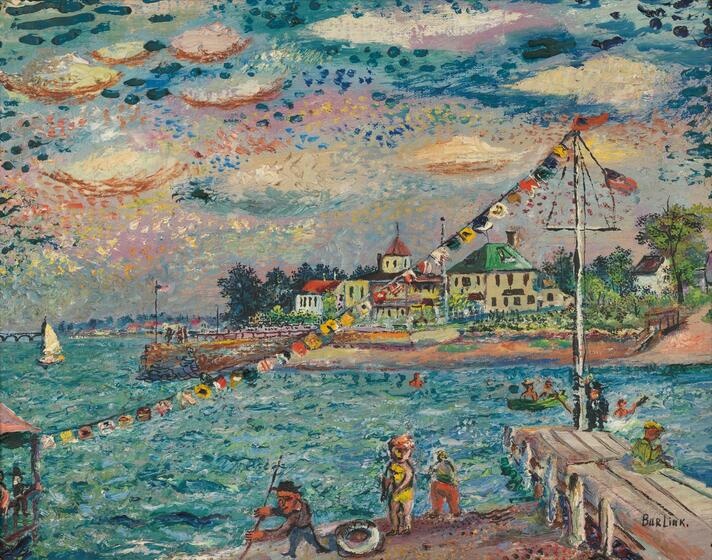

During this period, the artist became more active in exhibitions. He participated in several international group exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum; organized an open-air showcase of works in Washington Square; and began his cooperation with the ACA Gallery, which held a series of the artist’s personal exhibitions. Whitney Museum, Duncan Phillips the art scholar, and George Gershwin buy the artist’s work.

Despite his declared fidelity to the socialist idea, Burliuk’s life looks comfortably bourgeois in his memoir and correspondence of this period. He visits bohemian “parties” (using exactly this word in his correspondence), spends several weeks at the ocean escaping the summer heat, buys a motorboat for his son to go out on the Hudson River. The sons Burliuk calls Dave and Nicky, American style, graduate from a high school close to the new place on 15th street, and enter New York University.

32 Squiretown Rd Apt A, Hampton Bays, NY

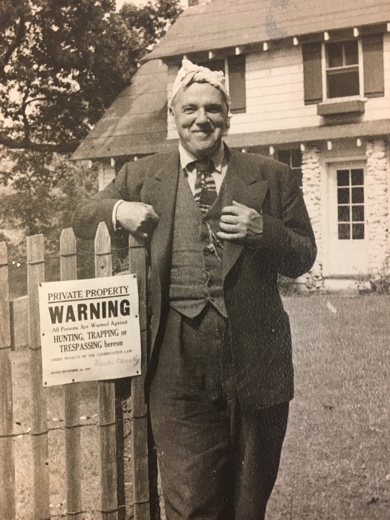

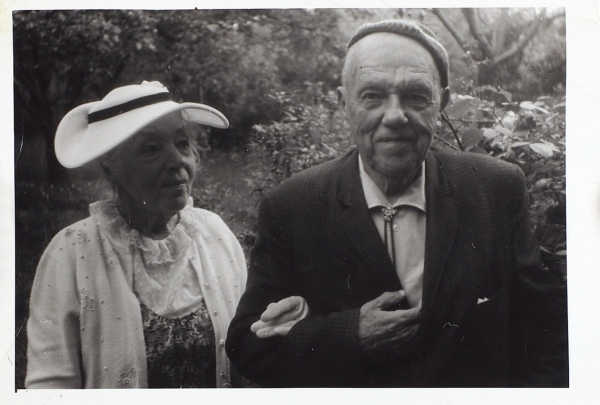

In 1941, David Burliuk and his family settled into a house in Hampton Bays on Long Island where his descendants still live. His long-standing dream of having a house on an ocean shore had finally come true.

Many artists gravitated towards Burliuk’s house. Soon, Raphael and Moses Soyer settled nearby, then Nikolay Tsitskovsky and George Constant. The artists uniting around Burliuk were called the Hampton Bays group. In 1953, the couple opened Burliuk Gallery in a small one-story building on a territory belonging to the family in Hampton Bays where works by the group were regularly exhibited.

The house, the workshop, the arbour in front of the house, and the living-room served as meeting places for Burliuk and his friends. “Russian parties” were often organized for the guests, with traditional Russian food, fun, the giving of long toasts, and songs sung accompanied on guitar.

However, the Burliuk couple did not spend a lot of time at their home on Long Island. Almost every year they escaped the cold New York winters for Florida, also travelling regularly to France, and visiting Czechoslovakia and the USSR despite his former motherland’s tepid welcome of the artist. In the USSR he was denied publication and exhibitions and there were insistent efforts to erase his name from the history of art.

When Burliuk was 80, he gathered his courage for a trip around the world, and in spring 1966 the 84-year-old artist opened a personal exhibition in London.

David Burliuk’s life teemed with activity until his death on 15 January 1967 at Southampton Hospital.