Boichuk Mykhaylo

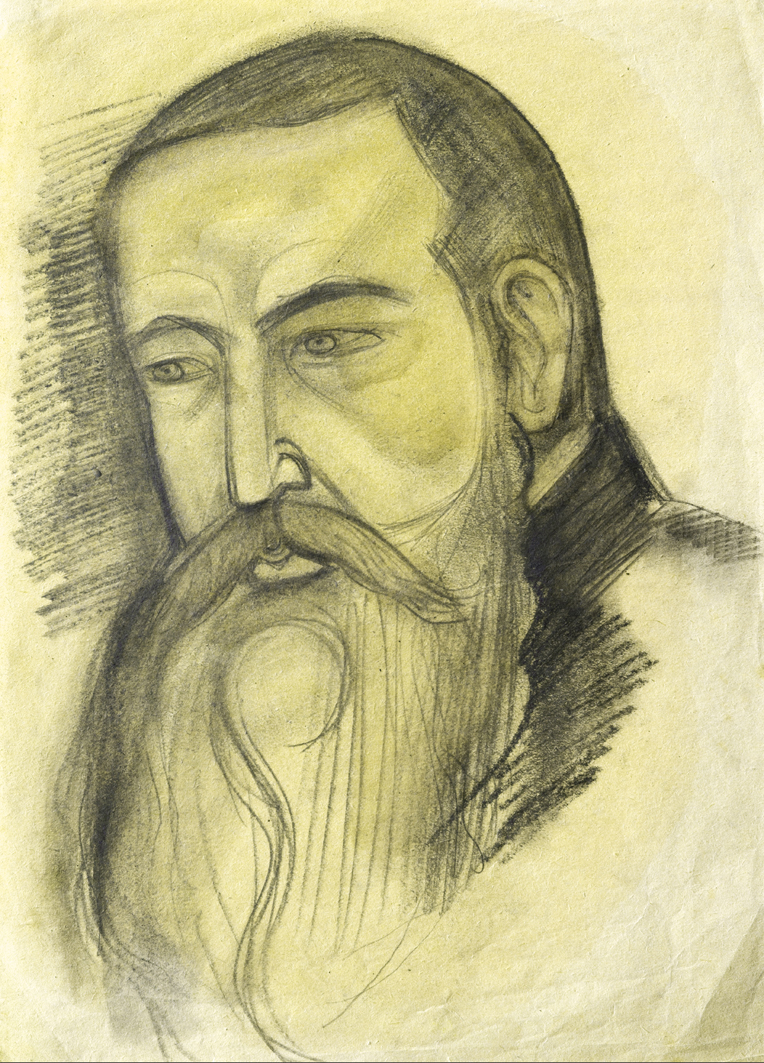

Mykhaylo Boychuk (1882-1937) is a monumental artist, restorer, and founder of the national style in art known as “Boychukism”.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Mykhaylo Boychuk did not try to break the connection with the old art and create something new from scratch. “For us, the work’s chronological date and origin are not important. Be it Egypt or the Renaissance, a Novgorod icon or a piece of African art, it does not matter. Art looks for the soil in the nation within which it is developing but when the artwork grows it becomes international. Can anyone follow those wide areas art is applied in and track down the masters it is created by? This is like water permeating everywhere and the same for everyone,” Boychuk explained to his students.

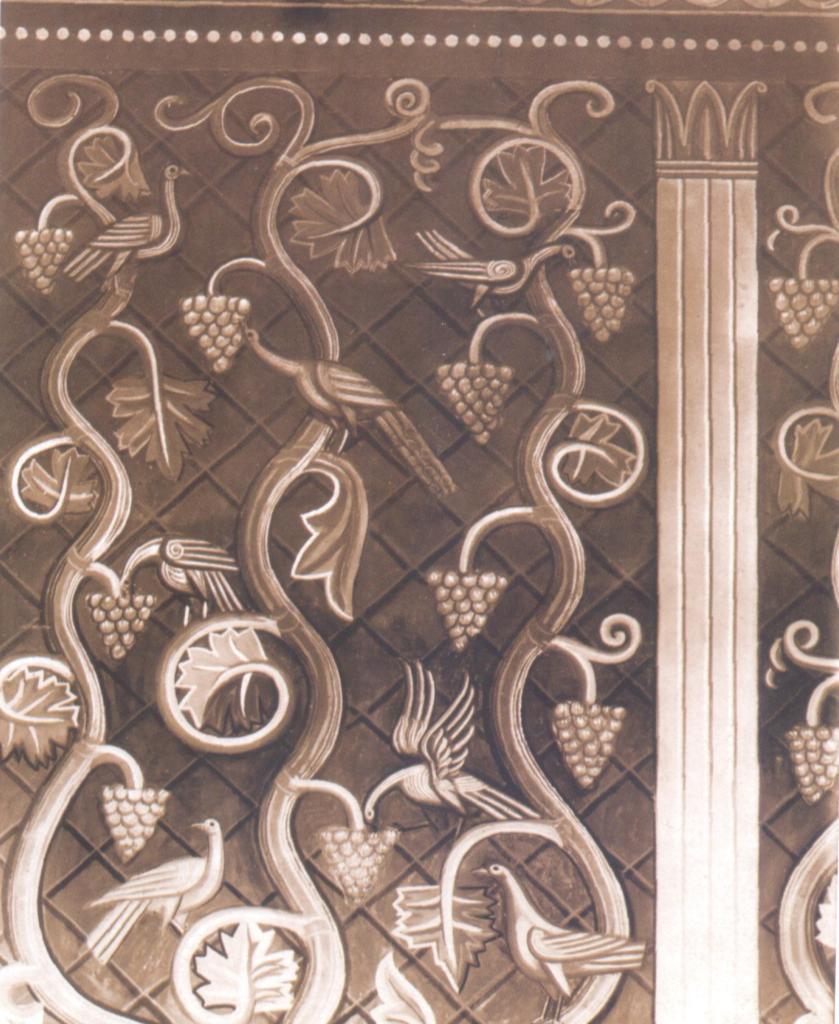

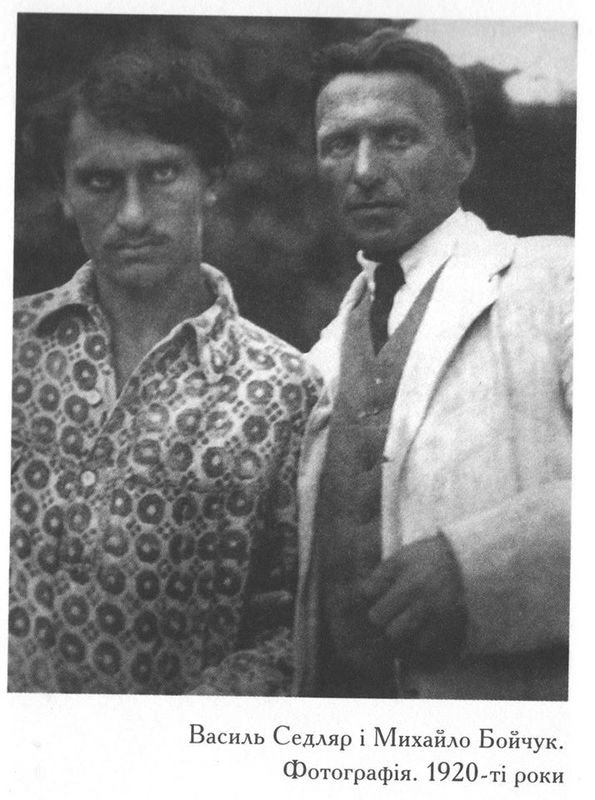

The artist was inspired by Byzantine art and combined its image system with the leading European trends and Ukrainian folk art, creating a single synthetic style alongside his students in which each type of art had to serve a common idea. Boychuk dreamed about art for the wider public creating the people’s living space: from walls to kitchenware, from books to furniture and rugs. Ideologically, his works did not run counter to the ideals of the 1917 October revolution, but the painting language was much too independent, much too pro-Western, much too formalist, so the government authorities considered Boychuk’s school harmful for the Soviet people and executed him in 1937 together with his wife Sofia Nalepynska-Boychuk and students Ivan Padalka and Vasyl Sedlyar.

Fortunately, his followers – “Boychukists” – became teachers themselves and made Boychuk’s ideas immortal through their students.

Nordbahnstraße 1, 1020 Wien, Austria

From May to October of 1899 Mykhaylo Boychuk, a gifted 17-year-old youth from a regular village family in Romanivka, Ternopil region, attended his first art studies in Vienna, the capital of Austria-Hungary.

In 1898, artists Ivan Trush, Yulian Pankevych and architect Vasyl Nahirny created an Association for Rusyn Art Development in Lviv which aimed to unite Ukrainian artists of Halychyna. Mykhaylo Boychuk received his first drawing lessons at the association. When his mentor, Yulian Pankevych, decided to go to Vienna to sit the exams for a lyceum teacher he took Boychuk along. The talented boy who knew he wanted to be an artist at the age of 12 was supported by a scholarship from the Taras Shevchenko Research Association in Lviv, a sort of Academy of Sciences that encouraged young talent.

As the artist himself later wrote, for six months he worked free of charge in the private school of some Vienna painter and mastered the painting craft. During this time, he learned a bit of German and diligently studied the exhibitions in local museums. His favourites were Fayum portraits, “the works by Greek artists brought up on Egyptian art”.

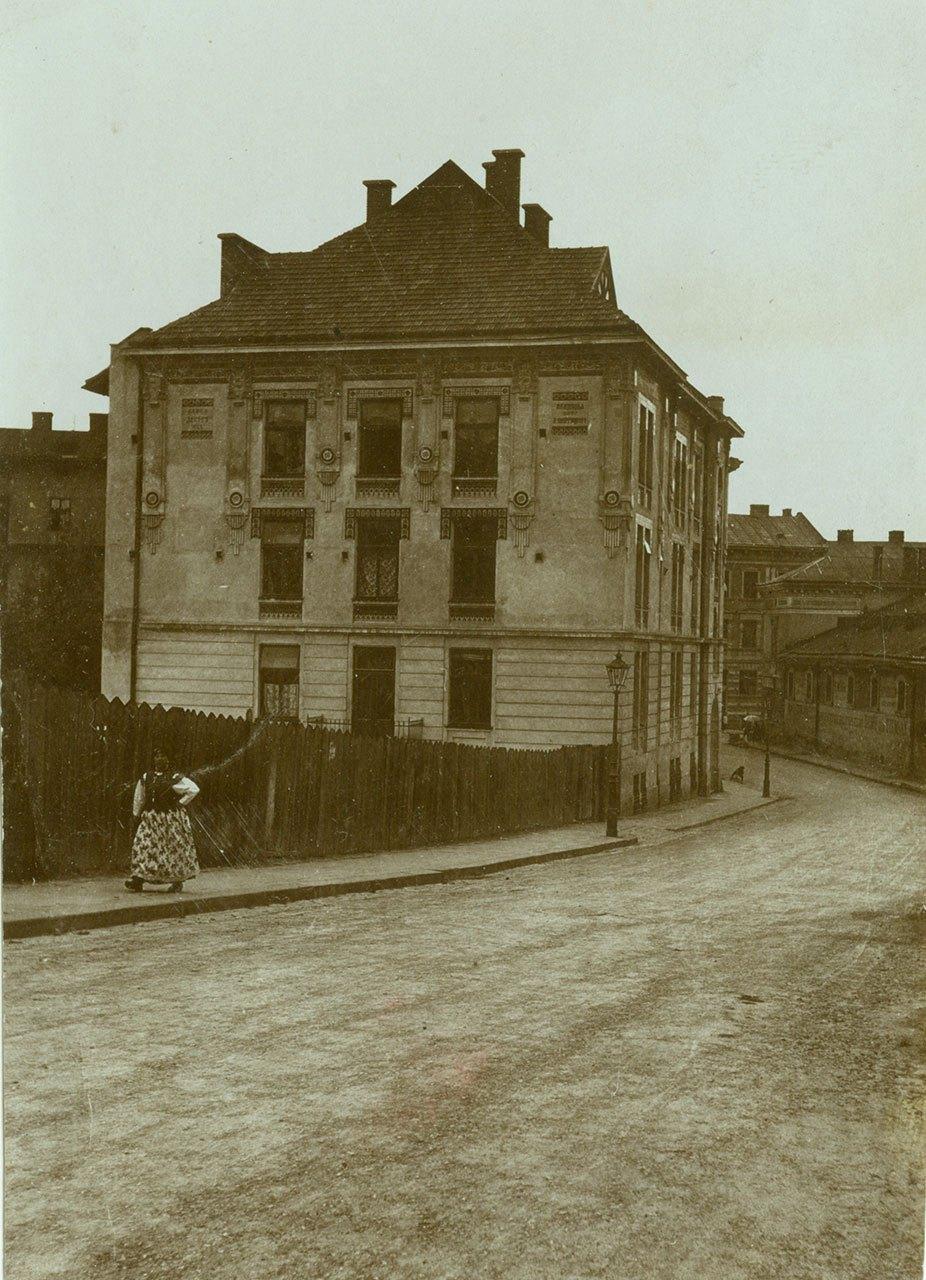

Rajska 6, Kraków, Poland

Five years of Boychuk’s studies at the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts were both a great professional school for the artist and a bridge of the gap in his general education. In 1899-1901, Boychuk rented accommodation at 6 Rajska street.

At that time Poland was living through a renaissance of national culture which was shaping into the literary and aesthetic movement “Young Poland”. Polish artists admired the aesthetics of modernism, symbolism and expressionism; they experimented with the combination of folklore, historicism, and modernism. Young Boychuk, observing this ascent of Polish literature, architecture, theatre and art, and living at the epicentre of creative search and discussions, analysed the state of Ukrainian art and reflected on preserving, popularizing and developing something of his own. Poles from Boychuk’s circles interested in Ukrainian culture, the Ukrainian community in Krakow congregating around Bohdan Lepky, professor of Ukrainian language and literature in Jagellonian University – all this encouraged the artist to ponder his national culture.

During his studies at the Krakow Academy Boychuk participated in exhibitions in Krakow and Lviv. His well-known portraits of that period were of Stefan Zeromski, a writer in whose building he lived for several months in Zakopane, a resort town, in 1904, and of Zeromski’s son Adam. Another Polish artist – a sculptor, a painter and an art scholar Stanislaw Witkewicz – wrote a recommendation letter to philanthropist and head of Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church Andrey Sheptitsky with a request for financial help for Boychuk. When Boychuk passed the letter to Metropolitan Sheptytsky he added a personal, oral request that the prelate also pay for his studies in Paris.

Akademiestraße 2, Munich, Germany

Andrey Sheptytsky, metropolitan of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and a patron to Halychyna artists, offered to pay for Boychuk’s studies at the Munich Academy of Arts. Mykhaylo reached Munich via Dresden where he familiarized himself carefully with the selection of old masters in the Dresden picture gallery.

In 1904-1905, he studied in Karl von Marr’s class. “Every day I draw in the Academy until noon, and from noon and on days off I do composition exercises at home or run to see exhibitions in the museum”, Boychuk wrote to his patron. In addition, he worked to improve his German and to closely follow the artistic life. In a letter written in August 1905 Boychuk enumerates the exhibitions he has seen: International, a huge exhibition of painting, sculpture and architecture; “Linbach’s collection”; Kunstgewerbe, a beautiful exhibition of crafts; Paolo Trubetsky’s sculpture exhibition; and besides, he writes, “one can always go to pinacothecas, Schack’s gallery, or the museum”.

The artist had to stop his studies in Munich Academy of Arts due to his conscription into the Austrian army; he spent the following year in the military service in Dalmatia (a historical region in the northwest of the Balkan peninsula). “Then in winter (1906-07) I returned to my dad,” the artist recalled. “He was happy to see me. We agreed then that I wouldn’t go to Munich anymore and instead would leave for Paris in spring.”

21 Rue Henry Monnier, Paris, France

In 1907, Boychuk’s dream about studying in Paris where new art was developing finally came true: Metropolitan Andrey Sheptitsky provided him with a scholarship. On the road Boychuk managed to see museum exhibitions in Vienna and Basel. On 13 April 1907 Paris roads welcomed the Ukrainian from the village who had already become an experienced connoisseur of the world art.

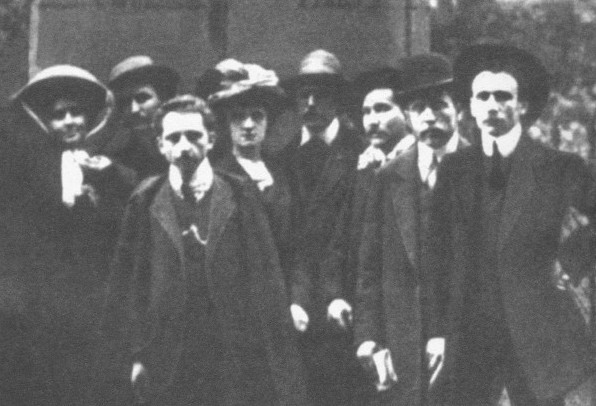

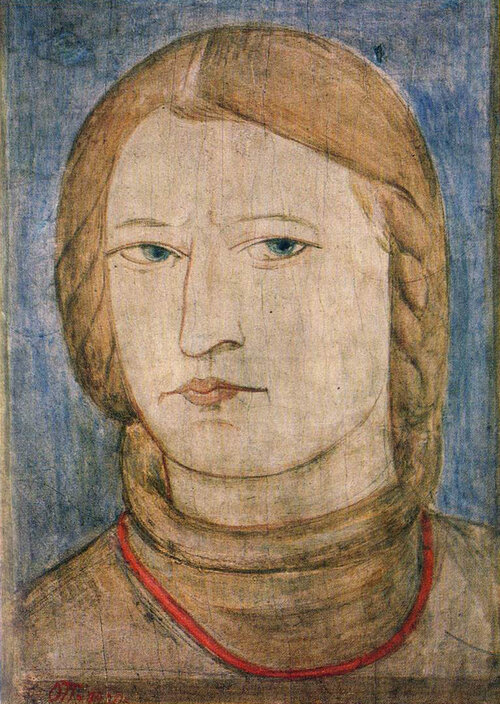

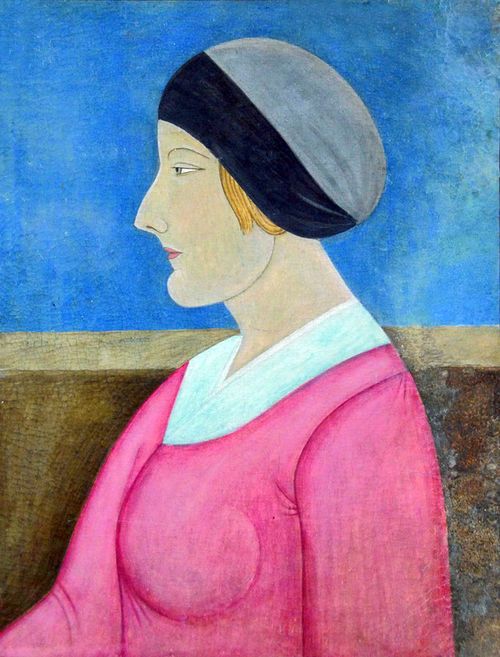

At first, Mykhaylo studied in Academie Vitti, in the class of Spanish artist H. Anglada. In 1908, Boychuk transferred to the Academie Ranson, founded by the Nabi art group – practitioners of post-impressionism and aesthetic descendants of Gauguin. While still in Lviv, Mykhaylo developed interest in Ancient Rus and Byzantine monumental art, so the practices of Nabists interested in monumental, folk and religious art were close to his heart. In Academie Ranson, the first “Boychukism school” formed, by Polish artists Sofia Segno, Sofia Nalepynska, Janina Lewakovska, Helena Shramm, Antoni Bushek, Zofia Bodouen de Courtenais, alongside Ukrainian painter Mykola Kasperovych.

“Already in 1908 a group of painters gathered around him; he worked with them in his workshop,” wrote Yevhen Bachynsky, a journalist, a diplomat and the first biographer of the artist. “It was like a real art factory because his ‘neo-Byzantine’ school, just like painting workshops of the medieval times, produced everything they needed, starting from paints, brushes, decks and frames and up to collective work on images and sketches. Paints produced in his workshop were known to many painters because they were not oil, but dyes mixed with plant extracts on egg yolk with garlic juice. The secret of making these paints had been lost long ago, and Boychuk is famous for bringing it back. He could freely paint with gold as with other colours and not employing the gold plates other painters opted for. He invented ‘a tempera’ painting style in use until 1420 and also an ‘al fresco’ wall painting approach on wet surfaces and ‘al secco’ on dry walls, diluting his paints in a warm wax solution. But what is especially important for world art – Mykhaylo Boychuk developed the foundation of real understanding for art, taking the Byzantine age as an example.”

As Mykhaylo Boychuk and his supporters drew an imaginary line of art from Byzantium to the early 20th century through the proto-Renaissance, Italy was first on his must-see list. While studying in Paris in 1907, Boychuk received an invitation from his Italian friend and spent two months in Venice, giving him enough time to carefully study the architecture and miraculous mosaics of the San Marco cathedral. In 1910, Boychuk spent several more months in Italy: he visited Florence, Venice and Ravenna, the latter filled with classical Byzantine frescoes and mosaics. The artist wrote the following in his letter to Yevhen Bachynsky: “… here I am wandering as if in a strange dream and looking at incredibly beautiful things. Via Florence I came to Ravenna, and now I am departing for Venice; in a week-and-a-half I will be back in Lviv.”

9 Rue Campagne Première, Paris, France

In 1908 Boychuk and his compatriots, artists Andriy Taran and Lev Kramarenko, rented a three-room apartment and workshop close to Jardins de Luxembourg. In the apartment opposite lived three female artists: Sofia Segno, Sofia Nalepynska, and Zofia Baudouin de Courtenay. The leader of the neo-Byzantines (as Boychuk’s club referred to itself) fell passionately fell in love Segno, only to marry Nalepynska soon after.

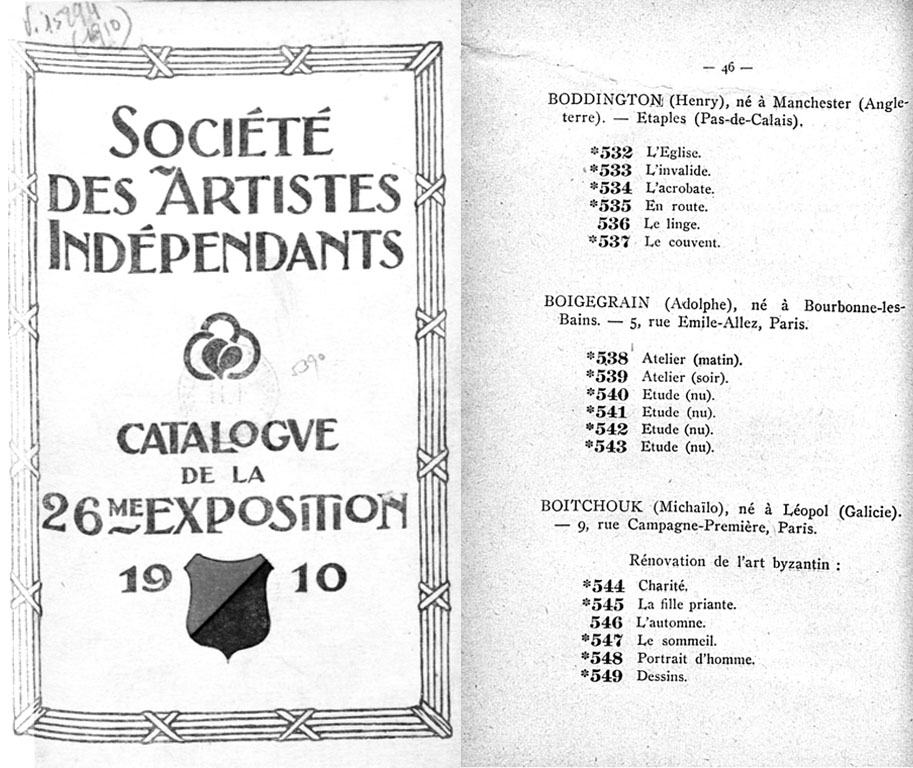

In 1909, two of Boychuk’s works were selected for the Autumn Salon: A Portrait of a Young Woman and Princess, and in 1910 at the Salon of Independents, the Restoration of Byzantine Art School (Boychuk, Kasperovych and Segno) debuts. In a separate room, they showcased 18 works united by the idea of restoring the principles of Byzantine art. It is worth noting that among approximately 5,000 exhibits their works were noticed and praised by many leading critics; newspapers in Paris, Krakow, Lviv and Saint Petersburg also wrote about them. Guillaume Apollinaire wrote: “This Little Russia group is an example of free wanderings between centuries. Until now, only poets have been able to do it, and now artists have shown their erudition. They travel between centuries and seem like decendants of Giotto and Cimabue.” The fans of new trends in art did not take to the works of the neo-Byzantines. Even Alexander Archipenko, an innovative sculptor, considered their search erroneous.

In addition to his studies Mykhaylo Boychuk participated in public life: in 1909, a Ukrainian community emerged in Paris; the artist was among eight founders of the community at the Establishing General Assembly. He was a rather active member of the Community, heading up the painting and carving department in the Art section, delivering lectures and singing in the choir. Boychuk and Kasperovych both sang tenor, Sofia Segno was an alto, and Alexander Archipenko a bass.

Cerkiew greckokatolicka pw. Przemienienia Pańskiego, Cerkiewna, Jaroslaw, Poland

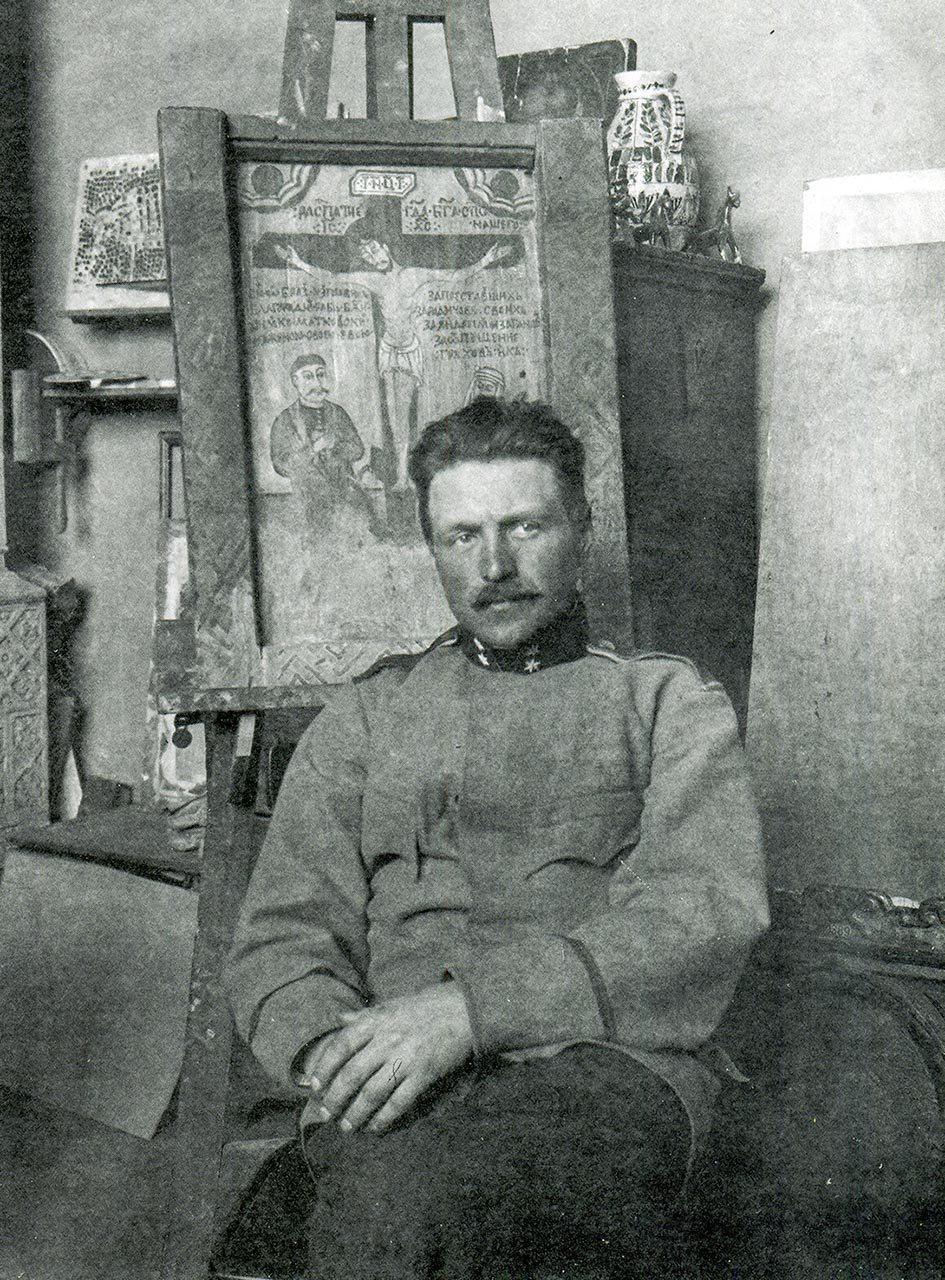

Having come back to Lviv in 1910, Mykhaylo Boychuk worked as a staff “icon preserver” in the newly created National Museum and as a monumental artist in Halychyna churches.

Museum director Ilarion Sventsitsky wrote the following: “Among Ukrainian artists in Lviv there was not a single one familiar with the technique of icon restoration […]. The arrival of Mykhaylo Boychuk in Lviv ended that. Ailing museum icons have finally found a real doctor. Mykhaylo Boychuk and his school worked mostly in the National Museum from 1910 till 1914 where he preserved a range of valuable icons from the 15th and the 16th centuries.”

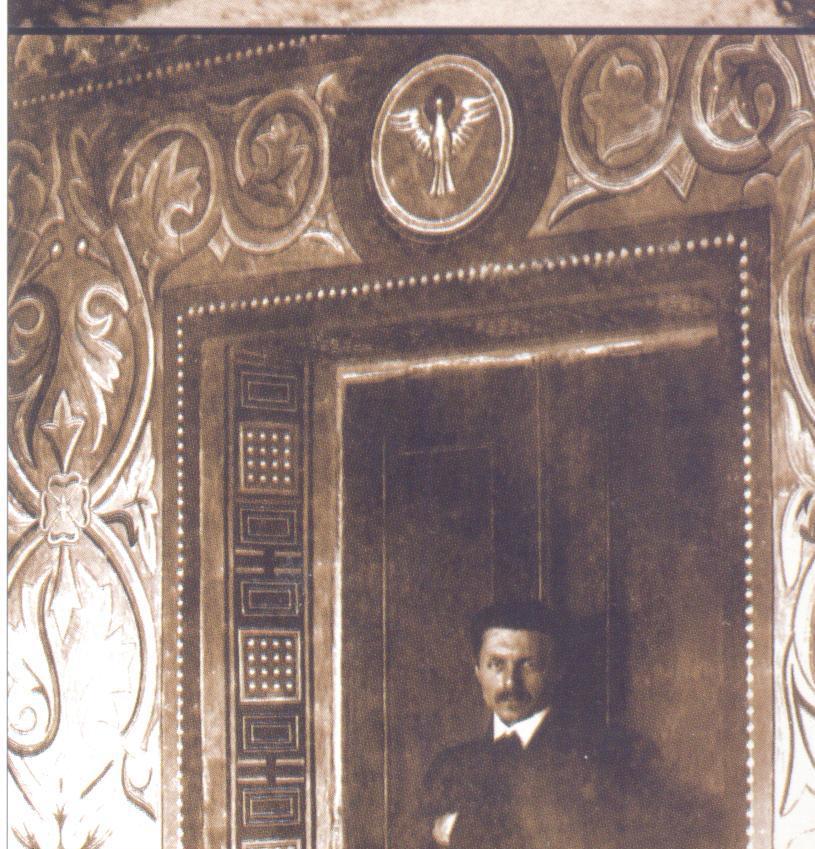

Mykhaylo Boychuk and his colleagues decorated the chapel of “Lector’s College” in Lviv, the Basilian Sisters monastery in Slovіtа (Zolochiv district). and a portion of the Transfiguration Church in Jaroslaw (now Poland) known for its miraculous icon of the Jaroslaw Holy Mother “Doors of Mercy”.

Between 1910–1912, new naves were added to the Greek Catholic Church of the Transfiguration built in 1714, using a design from architect M. Dobryansky. Some experts believe that Boychuk decorated the additional space, though others say he worked on a portion of the altar area. After several restorations it is hard to establish that for certain. V. Vygnanets, a relative of Boychuk from his mother’s side, writes about this work in his memoir: “A year or two before the war we painted the Church of the Transfiguration in Jaroslaw and in the village next to Krynytsya. I assisted him a bit because I had been passionate for art since my youth.” According to Boychuk’s contemporaries, the artist was not satisfied with his work in Jaroslaw; he believed that he did not fulfil the task properly as his decorations did not really match the old murals.

Veliky Novgorod, Novgorod Oblast, Russia, 173000

Captivated by Byzantine art, Boychuk knew not only the ideological principles of Ancient Rus art but also its technical side: this is why he prepared the foundation and dyes himself, mastering tempera along with “al fresco” and “al secco” techniques. Soon afterwards he became the sole expert restorer of frescoes within the Russian Empire. Jumping at the opportunity to meet Sofia Nalepynska’s parents in Petersburg, Boychuk studied the monuments of Moscow, Petersburg and Novgorod. Meanwhile, the Russian Architectural Association commissioned Boychuk with the restoration of the altar-screen at the Three Saints Church in Lemeshi, near Kozelets. Mykhaylo Boychuk and his wife Sofia Nalepynska, as well as Zofia Baudouin de Courtenay, spent the summer and autumn of 1911 in Lemeshi. From Kozelets the artist regularly travelled to Kyiv, met Ukrainian artistic leaders and culture figures, consulted on the restoration of Ancient Rus churches. Later while working in Kyiv, Boychuk participated in refreshing frescoes in St Sofia’s cathedral and restoration of the Yelets monastery in Chernihiv.

Chapaev Street 22/1, Uralsk, Kazakhstan

Mykhaylo Boychuk and his younger brother Tymish spent 1914-1917 in exile: during World War I, being Austrian citizens (and therefore from an enemy state), they were deported by the Russian police—first to Uralsk, then to Arzamas, and isolated. From the stories of his contemporaries, we know that this was a hard time for the brothers, with a period marked by hunger, arrest, and cruel treatment from the administration. Dmytro Antonovych, author of the first history of Ukrainian art, wrote that in exile Boychuk continued his teaching with brother as his student. Three works by Tymofiy Boychuk are known: Two Women with Seeds, A Scene from the Market, and A Town Street, dated 1916. The February revolution in Russia ended their exile, and in late 1917 Boychuk found himself among the founders of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts in Kyiv.

Volodymyrska St, 57, Kyiv, Ukraine

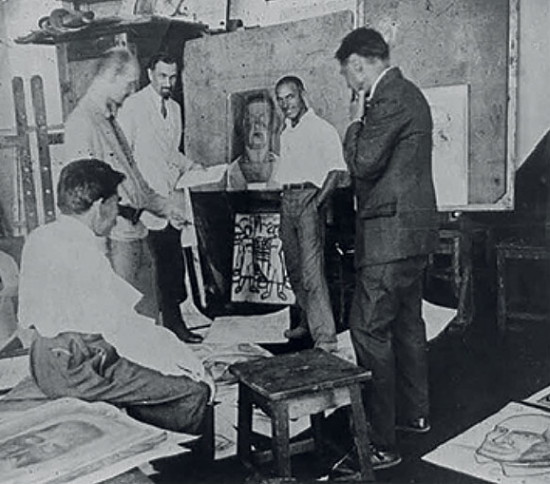

Unexpectedly to him, (but with thanks to Dmytro Antonovych’s recommendation) Mykhaylo Boychuk became one of the eight founding professors of the first Ukrainian art university, the Ukrainian Academy of Arts. At the exhibition of professors opening on 5 December 1917, Boychuk presented his work before a Kyiv audience for the first time. The artist headed the fresco and mosaics workshop, later renamed as the monumental art workshop. It was attended by Sergiy Kolos, Oksana Pavlenko, Ivan Padalka, Vasyl Sedlyar, Maria Trubetska, Katrya Borodina, Emmanuil Shekhtman, Antonina Ivanova, Kostyantyn Yeleva, and Onufriy Bizyukov. In 1921, Boychuk’s student and follower Mykola Kasperovych also came to teach in the Academy; in 1922, Sofia Nalepynska-Boychuk joined the staff. All of them later will be referred to as Boychuk’s school—the Boychukists.

Boychuk’s students studied and worked side-by-side with their professor: the artist followed the work procedures of a medieval workshop. They analysed Giotto’s works, Ravenna mosaics, and Byzantine frescoes for hours, singling out composition schemes and structural elements. “This drill,” Vasyl Sedlyar wrote, “that was severely hammered into young artists never prevented their peculiarities from showing up. Raphael, a student of Perugino, still became the incredible Raphael.”

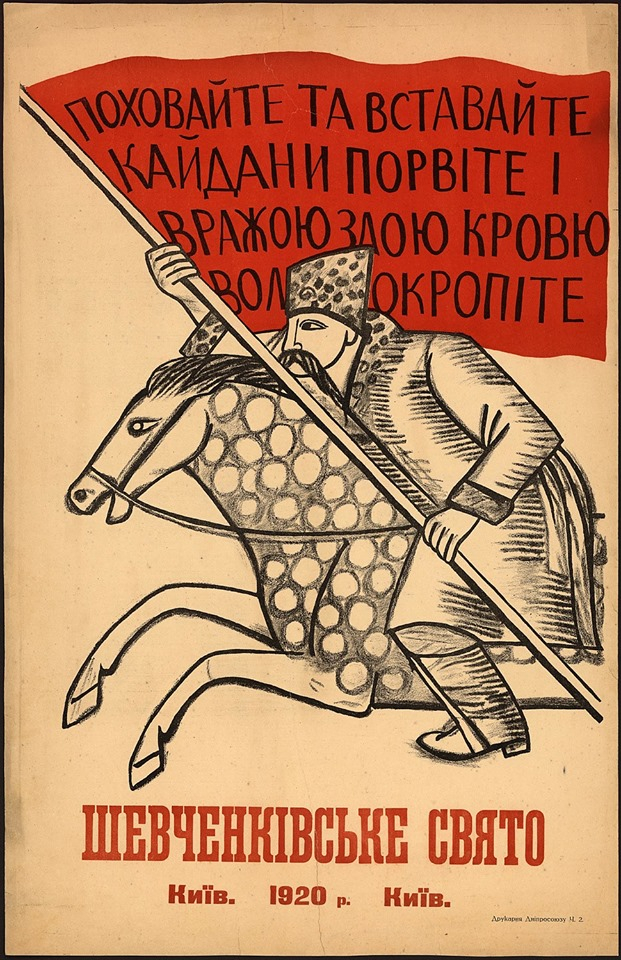

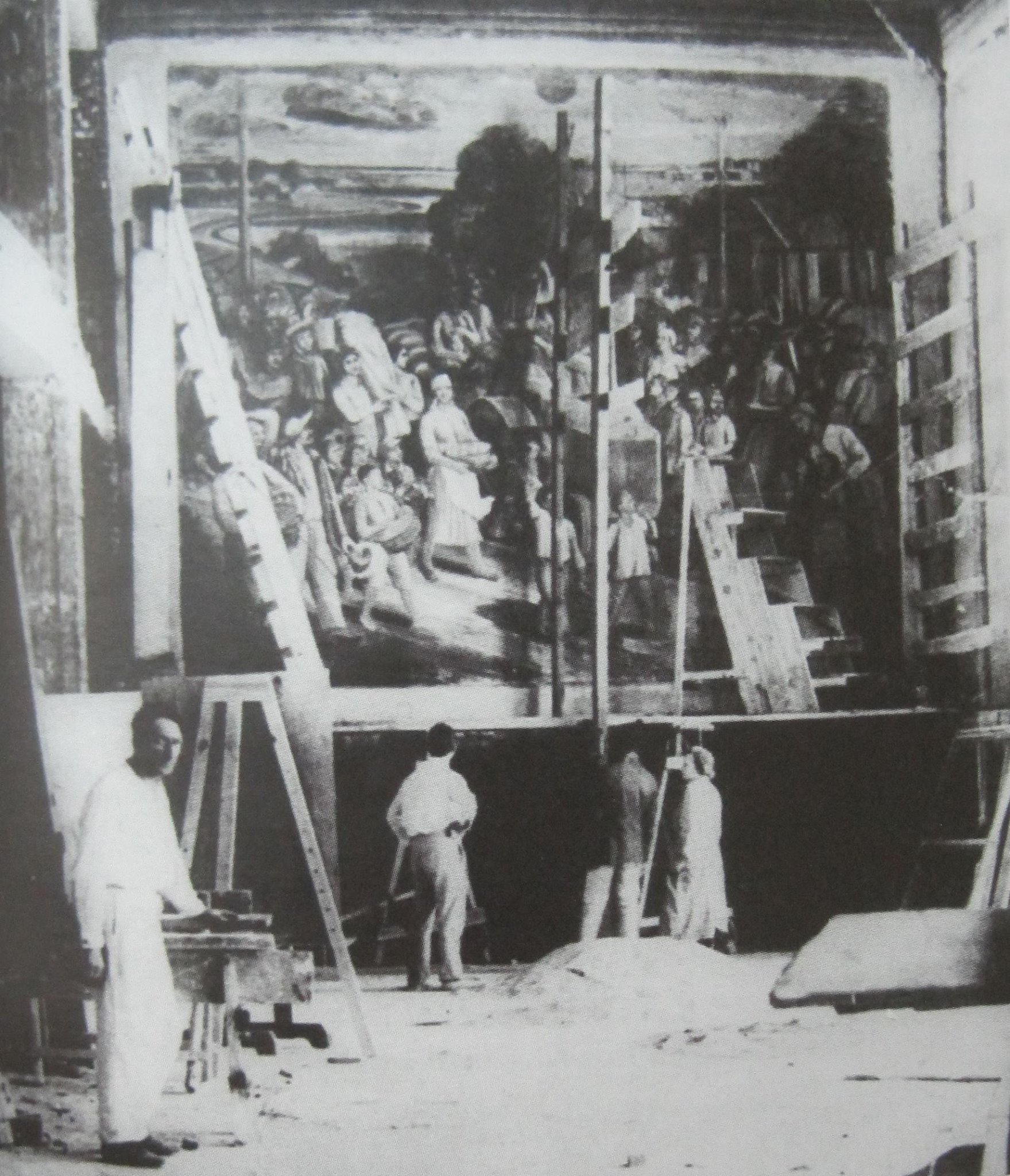

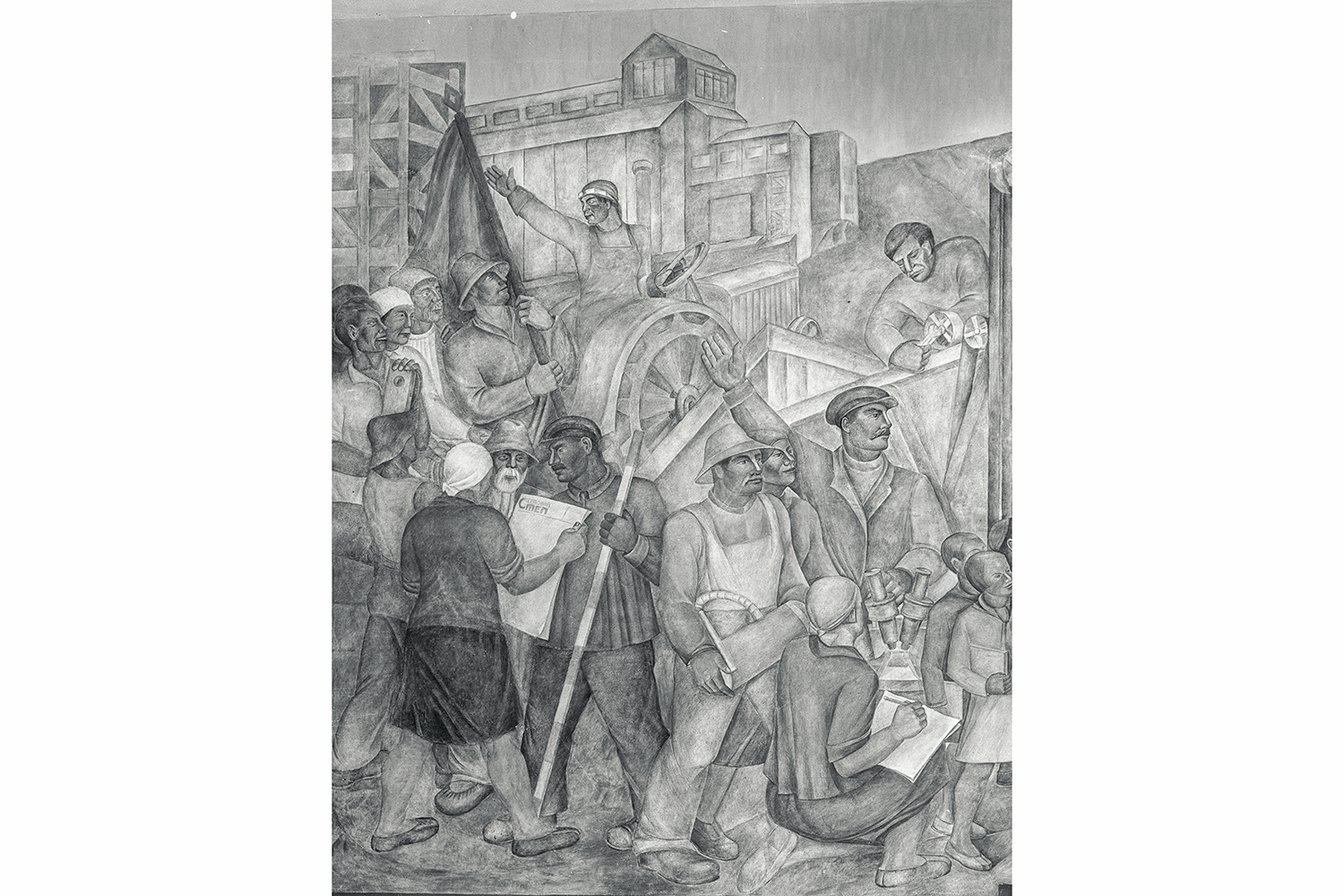

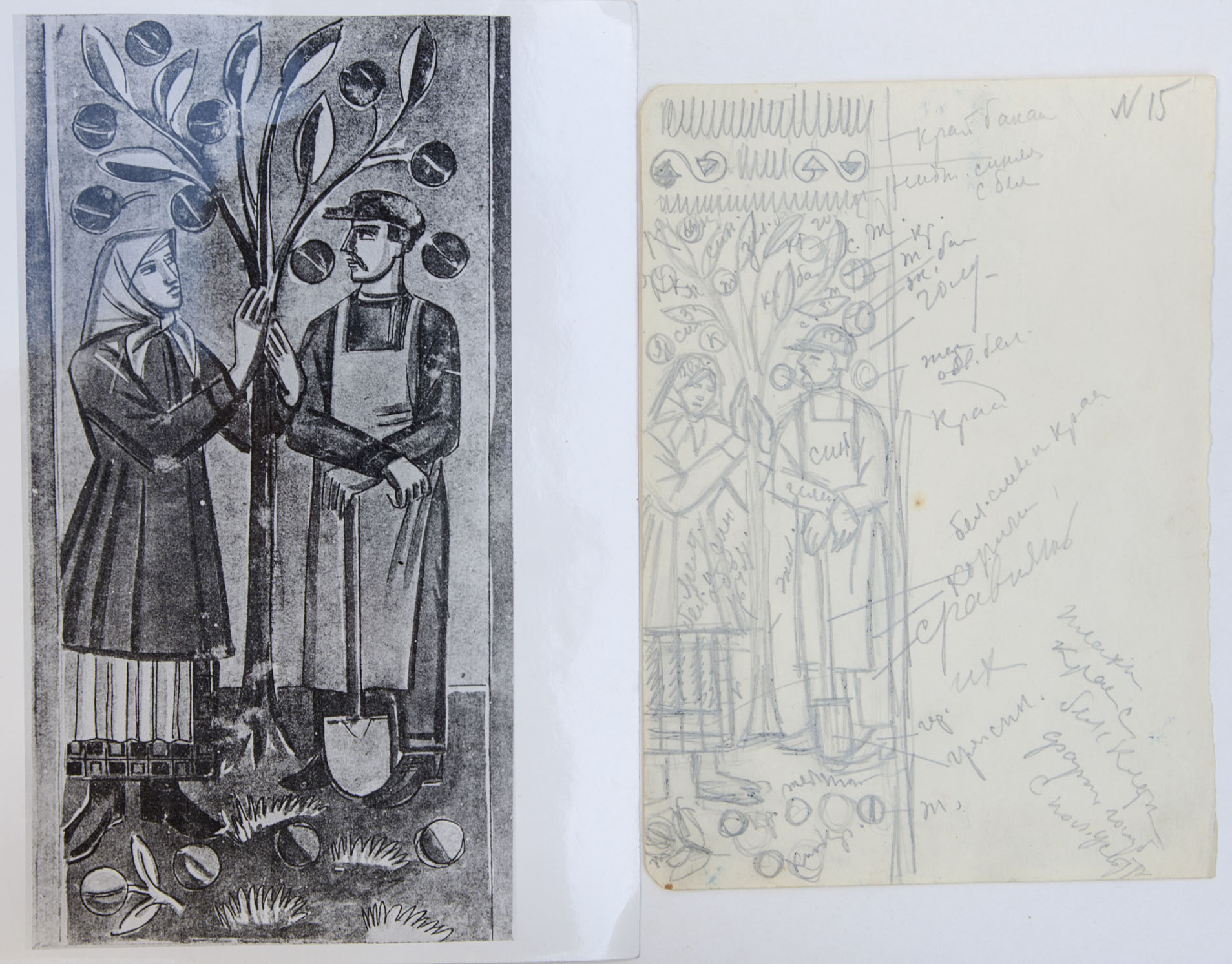

At that time, Mykhaylo Boychuk became closer to avant-garde theatre director Les Kurbas and created the stagecraft for several of his productions. In 1920, he was appointed the head of First State Art Workshops in Kyiv which featured lots of space for Boychuk’s “monumental” ambitions: he and his students decorated the Bolshevik, a propaganda ship; worked on the opera theatre for the assembly of local governments; painted the walls of Lutsky barracks in Kyiv—the first ensemble of monumental art in the 20th century. Heroic plots, villagers’ work, Mamay, military theme—the Boychukists produced 14 compositions on the barrack walls. Sadly, these were destroyed during renovations in 1922.

The Boychukists also produced several more frescoes: at the resort in the Khadzhibey estuary in Odesa (1928); for the State Political Administration in Odesa (1930-1932); and the Chervonozavodsky theatre in Kharkiv (1933-1935). These, too, were all lost, and the Boychukis heritage is currently only represented by several easel paintings and graphic art pieces.

In 1928 in Moscow, Mykhaylo Boychuk met Diego Rivera, a famous Mexican mural artist, and in their conversations they came to understand that they worked according to the same principles and philosophy of art: a combination of novel European art and national painting traditions yields a new quality to monumental art, which is the best fit for the demands of the revolutionary age.

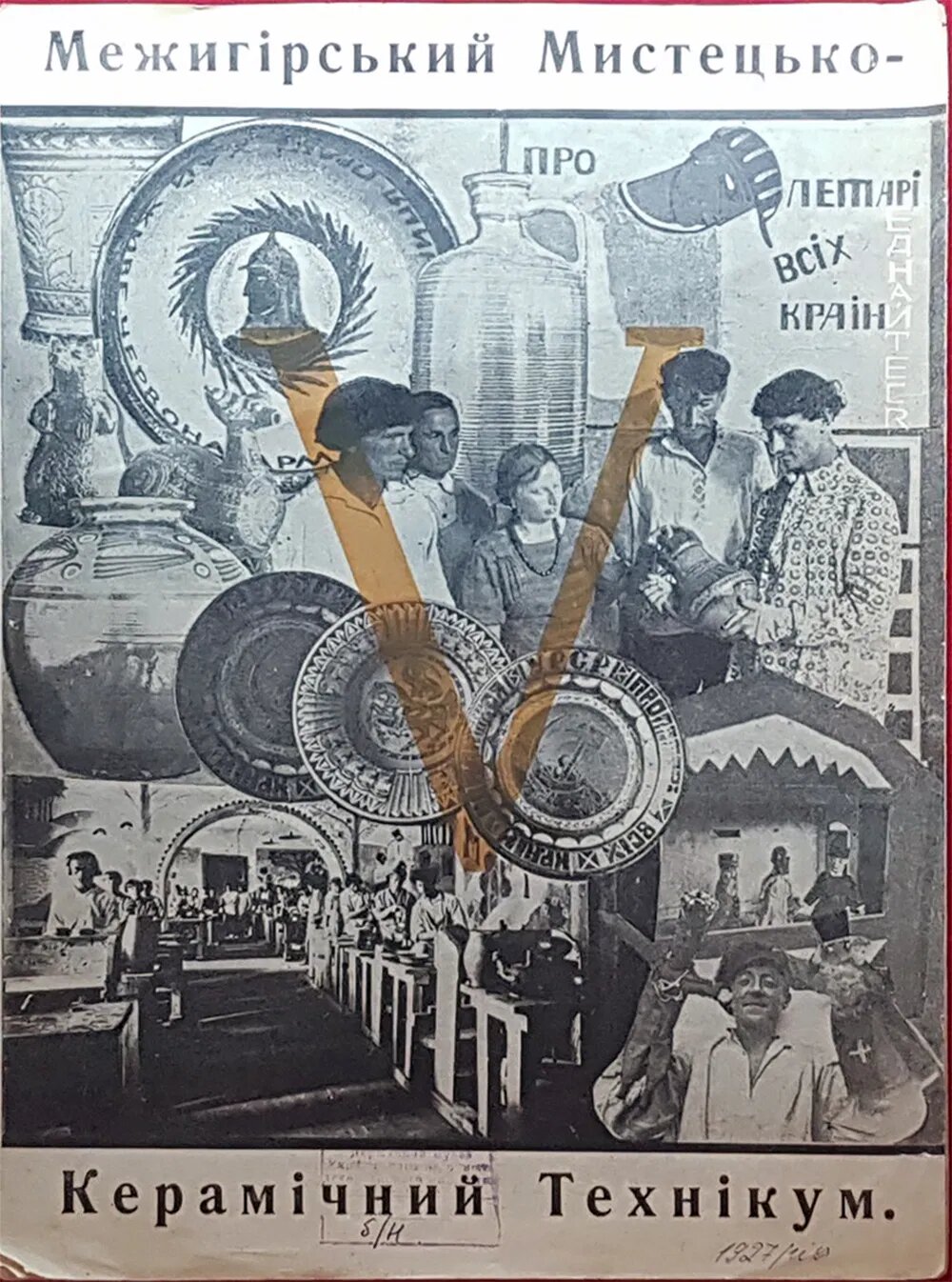

Gropiusallee 38, 06846 Dessau-Roßlau, Germany

Mykhaylo Boychuk believed that artists have to create a single style for the people’s living space: interiors, household art, furniture, kitchenware and carpets. And in 1926 Mykhaylo Boychuk, his wife Sofia Nalepynska-Boychuk, and Vasyl Sedlyar, who had been the head of Mezhyhirya ceramic college since 1923, went on a business trip to Europe to learn the craft of leading Western workhouses in combining technology and art. In Germany they visited Reismann’s factory which produced equipment for ceramic production and a Bauhaus design school in Dessau. In France they went to a china workhouse in Sevres and Leising’s ceramics factory. In Italy they studied the production of majolica in Faenza, Urbino and Gubbio, and ceramics in Sicily. The artists returned home via Vienna and Prague where they delivered several lectures.

In 1936, when Boychuk was arrested, these trips became one of the formal reasons for arrest and accusations of spying. In his case, to see Paris and then to die is not a figure of speech. In 1937, Boychuk, Nalepynska-Boychuk, Padalka and Sedlyar were executed. In 1958, they were politically rehabilitated but up until the end of the 1980s, work by the Boychukists were banned.

University Embankment, 17, Saint Petersburg, Russia

At the close of the 1920s artistic circles and the press began claiming that the Boychukists were reactionaries. Leftist artists accused Boychuk of stylizing and archaism, decorativeness and formalism, further criticizing him for studying abroad supported by the funds of a Greek Catholic church leader. They say that Kazimir Malevich told Boychuk: “You paint modern workers like saints on icons. There is a mismatch here. It would be the same for Ramses II to speak on the telephone or for a contemporary tailor to make a tuxedo for Jesus Christ.” Boychuk did not feel comfortable at the academy any longer, and in 1930 he left for Leningrad (now Petersburg) to teach in the composition department at the Institute of Proletarian Art. The talented artist and experienced teacher was chosen as department chair. “… It is much easier for me to work here than in Kyiv,” he wrote to Oksana Pavlenko.